COVID Part Two: Why I Trusted the Vaccine – and Why I Changed My Mind

When the COVID-19 vaccines were first announced, I was relieved. Grateful, even. After months of global panic, lockdowns, and conflicting expert opinions, the vaccines seemed to offer what we all desperately wanted: a way out.

I wasn’t a “vaccine enthusiast,” but I wasn’t skeptical either. Like most people, I grew up accepting that vaccines were part of what made modern medicine so successful. Polio, smallpox, measles – these had been deadly diseases until vaccines helped bring them under control or, in some cases, eradicate them. I got my flu shot most years. I had my childhood immunizations. And when COVID arrived, I watched with interest, not suspicion, as companies raced to develop a new kind of vaccine for a novel virus.

I followed the early news: the record-breaking speed of development, the glowing headlines about efficacy – “95% effective” said one press release after another. I also noticed how quickly the idea of “herd immunity” became associated with getting a shot. Protect yourself. Protect others. Return to normal. The appeal was hard to ignore.

By the time the vaccines were available to the public, I had made up my mind. I got my first shot in the spring of 2021 and followed up with the second dose a few weeks later. I didn’t do it because I was worried about dying from COVID. Based on what I had already read about the virus and my personal risk factors, I wasn’t especially concerned about that. I got the vaccine because I believed it was safe, effective, and the responsible thing to do.

And then – shortly after my second dose – I had a stroke.

It came without warning. No history of strokes, no family predisposition, no red flags. I had a blockage in my left carotid artery. I was lucky to survive. I was even luckier to recover most of my faculties. But as I lay in the hospital bed, the question kept looping through my mind: Could the vaccine have caused this?

Doctors were careful not to speculate. And I didn’t want to jump to conclusions. But I also couldn’t ignore the timeline. I had been healthy. Then, within days of my second dose, I wasn’t. That was the beginning of my doubts.

In the months that followed, I began to look more seriously into claims being made about the vaccines: that they stopped transmission, that they were “safe and effective” for nearly everyone, and that side effects were “exceedingly rare.”

I read everything I could get my hands on, including newspaper articles, magazine stories, precis from scientific journals, and reports from about a dozen doctors and scientists that were skeptical of the claims mentioned above.

I was reading six or eight pieces a day and filing under in the obvious categories: safety, effectiveness, government announcements and proclamations, and media coverage. Initially (and understandably) most of what I was reading were positive reports from the government, the legacy media, and the pharmaceutical industry. But as the weeks and months passed, I was reading some worrisome reports that contradicted the official narrative.

Increasingly, evidence was emerging that the vaccines were not nearly as effective as claimed at both reducing the chance of contracting COVID and reducing its infectiousness.

It soon became clear that the vaccines had become a political issue, with one side arguing that they were not only safe and effective but also necessary to keep the total count of deaths down.

And then I noticed a new tactic on the part of those that supported mass vaccinations. Dissenting voices were being shamed, silenced, and censored.

Caution was equated with selfishness. Uncertainty was rebranded as “misinformation.” And ordinary people – like me – who had experienced something unexpected or wanted to ask questions were treated as a problem to be managed rather than as participants in a shared search for truth.

This essay is not an anti-vaccine rant. It’s not a conspiracy manifesto. It’s also not a medical treatise. I’m not a virologist, and I don’t pretend to be one. I’m a writer. I try to pay attention. I try to be honest about what I see and what I learn. And what I’ve seen, since 2021, has forced me to reconsider nearly everything I thought I understood about modern medicine, public health, government messaging, and risk.

As you may recall, Part One of this monograph was about the virus itself – how early reporting, flawed assumptions, and poor communication distorted our understanding of the COVID-19 threat.

This second part will be about the vaccines. A fact-based look at what we were told about them, how that differed from what was being said, how this campaign of disinformation came about to validate them, and why.

It begins with my own story. But it doesn’t end there.

Chapter 1. The Promise: Safe, Effective, and Our Best Hope

In late 2020 and early 2021, the message from government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and the media was remarkably consistent: The COVID-19 vaccines were not just a medical breakthrough. They were a miracle.

The language was bold and reassuring. The vaccines, we were told, were “safe and effective.” They would protect individuals from contracting COVID-19. They would help prevent the spread of the virus to others. They would end the pandemic and allow society to return to normal life.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), declared in December 2020 that the vaccines were “extraordinarily effective.” President-elect Joe Biden promised that mass vaccination would lead to “a future that is brighter.” Leading media outlets ran headlines like:

* “Pfizer and Moderna Vaccines 95% Effective, Early Data Show” (New York Times, Nov. 2020)

* “Vaccines Are the Fastest Way Back to Normal” (Washington Post, Jan. 2021)

* “Experts Agree: Vaccines Will End the Pandemic” (CNN, Feb. 2021)

Public health campaigns emphasized urgency. Commercials and public service announcements encouraged people to get vaccinated not just for themselves but for their families, their communities, and the country. Slogans like Get Vaccinated: Do Your Part and One Shot Closer to Normal appeared on buses, billboards, and television screens.

The initial rollout strategy relied heavily on these ideas:

* Effectiveness: Clinical trials reported very high efficacy against symptomatic COVID-19 – about 95% for Pfizer-BioNTech and 94.1% for Moderna.

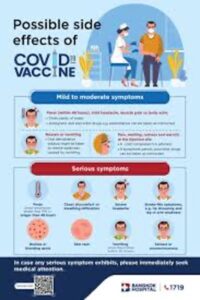

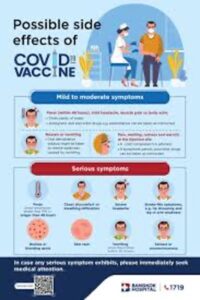

* Safety: Side effects were portrayed as minor and short-lived – sore arms, mild fever, fatigue.

* Social Responsibility: Getting vaccinated was framed as an act of altruism, protecting the vulnerable and hastening the end of lockdowns.

For many, including me, this messaging seemed credible. The vaccines had been reviewed by the FDA under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), which suggested a degree of rigorous evaluation. We were told that no steps had been skipped in the development and testing process, despite the unprecedented speed of production.

Operation Warp Speed, launched by the Trump administration, was praised for facilitating rapid development without compromising safety protocols. Scientists and regulators appeared together at press conferences, offering assurances that the vaccines were the product of decades of prior research into mRNA technology, not something invented overnight.

Moreover, the numbers appeared persuasive. Early data suggested that vaccinated individuals were far less likely to be hospitalized or die from COVID-19. That was powerful reassurance, especially for older adults and those with pre-existing conditions.

In this context, choosing to get vaccinated felt both prudent and civic-minded. It wasn’t a political decision – at least, not yet. It was simply common sense based on the best available evidence. The promise was clear:

* The vaccine would protect me.

* It would help protect others.

* It would speed the return to normal life.

And there was little public discussion – at least at first – about possible downsides. Serious adverse effects were said to be vanishingly rare. Long-term risks were dismissed with statements like “there is no biological reason to expect problems down the line.” In effect, the public was encouraged to think of the vaccines as if they were seatbelts: overwhelmingly safe, smart, and essential.

Few paused to ask whether the early clinical trials, which lasted only a few months, could truly reveal long-term outcomes.

Fewer still pointed out that Emergency Use Authorization, by its very nature, involved a gamble – a calculated risk based on incomplete data.

Looking back, it’s clear that much of the public’s trust – my trust – was built not just on scientific claims, but on the certainty with which those claims were delivered. The tone was emphatic, the confidence absolute.

There was little room for nuance.

No admission that we might discover problems later.

No acknowledgment that a novel technology (mRNA vaccines) being deployed at global scale for the first time might hold unknown risks.

Those doubts, where they existed, were kept far from the public conversation. Instead, the promise was repeated, louder and more frequently.

And for a time, I, like millions of others, believed it.

Chapter 2. The Cracks Begin to Show

For a while, it seemed like the vaccines were living up to the hype. Case numbers fell. Hospitalizations dropped. People started traveling again, gathering again, living again.

But by the summer of 2021, reports started trickling in that fully vaccinated people were still catching COVID. The term “breakthrough case” became part of the public vocabulary.

At first, these cases were described as rare exceptions – statistical outliers that didn’t undermine the overall promise.

Breakthrough infections are exceedingly rare,” CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said in an April 27, 2021 interview. “The vaccines are working.”

But the numbers told a different story.

In July 2021, an outbreak in Provincetown, Massachusetts, made headlines: Nearly three-quarters of the COVID cases linked to crowded July 4th festivities occurred among the fully vaccinated. A CDC report published on July 30, 2021 (MMWR Weekly) acknowledged the findings and quietly revised its internal guidance, noting that vaccinated individuals could transmit the virus.

The messaging shifted almost overnight.

Instead of promising prevention of infection, the authorities now emphasized protection against severe disease.

Dr. Fauci, in an interview on Meet the Press (Aug. 1, 2021), said: “The vaccines are doing what we intended them to do – to prevent severe disease, hospitalization, and death.”

That was a significant change. But rather than admit that public expectations had been set too high, officials largely framed the pivot as a natural evolution of science.

Critics noticed. Dr. Marty Makary of Johns Hopkins wrote in The Wall Street Journal on Aug. 2, 2021:

“Public health officials owe the public an honest accounting of vaccine limitations. Pretending that breakthrough infections are insignificant does more harm than good.”

Meanwhile, concern over vaccine side effects was building.

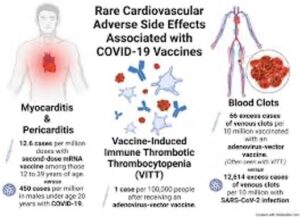

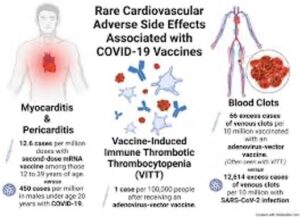

On April 13, 2021, the CDC and FDA recommended a nationwide “pause” in the use of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine after reports of six cases of a rare blood-clotting disorder, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), among women aged 18 to 48.

Though six cases may seem small, they occurred among 6.8 million doses administered – enough to warrant alarm.

The pause was lifted after 10 days, but trust, once shaken, wasn’t easily repaired.

Even more concerning was the emerging data on myocarditis and pericarditis – inflammation of the heart muscle or surrounding tissue – especially among younger males following mRNA vaccination.

In June 2021, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) acknowledged the connection.

The CDC reported 1,226 cases of myocarditis or pericarditis among people aged 16 to 24 after mRNA vaccination – substantially higher than the expected background rate.

A joint statement by the CDC and HHS described the risk as “extremely rare,” but the agency updated its vaccine fact sheets to include warnings about myocarditis and pericarditis, particularly after the second dose.

Dr. Vinay Prasad, a hematologist-oncologist and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, was among early skeptics. He wrote in MedPage Today (June 28, 2021):

“Young men have a non-trivial risk of vaccine-associated myocarditis. The CDC should be clearer about that risk and let people make informed decisions.”

Similarly, the British Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization (JCVI) took a more cautious approach. In Sept. 2021, the JCVI advised against vaccinating healthy 12- to 15-year-olds with mRNA shots, citing the low risk of serious illness from COVID and the emerging myocarditis data.

It was a rare public break from the American approach.

Meanwhile, new studies complicated the case for durable vaccine protection.

A Qatar-based study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in Oct. 2021 showed that vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic infection from the Delta variant declined sharply over time, falling to as low as 20% by six months post-vaccination. Protection against severe disease remained high – but the notion of lasting immunity against infection was effectively debunked.

The Israeli Ministry of Health reported similar findings as early as July 2021: Among fully vaccinated individuals over 60, effectiveness against infection had dropped to 39%.

Israel, once a model for global vaccination success, responded by launching the world’s first booster campaign in August 2021 – just eight months after its initial vaccine rollout.

Yet here in the US, booster discussions initially faced resistance. Officials worried that talking about waning effectiveness might fuel vaccine hesitancy.

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, warned:

“The perception is going to be that the vaccines are failing. They’re not failing. Protection against severe disease is holding.”

Maybe so.

But the public had been promised something closer to immunity – not merely an insurance policy against hospitalization.

All the while, questions about serious side effects persisted – not just myocarditis, but also reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome (linked to Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine), thrombocytopenia, and severe allergic reactions.

Authorities continued to insist that the benefits outweighed the risks, which for most people was probably true. But by now, it was impossible to deny:

* The vaccines didn’t reliably prevent infection.

* They didn’t reliably prevent transmission.

* They carried real risks – especially for specific demographic groups.

Still, the public messaging didn’t shift to match the evidence.

Mandates were introduced across workplaces, schools, and travel industries as if the original story still held up intact. Slogans like Get Vaccinated to Stop the Spread were still everywhere – long after it was clear that vaccinated individuals could and did spread the virus.

Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, a Stanford epidemiologist and co-author of the Great Barrington Declaration, summarized the situation bluntly in a Newsweek op-ed (Nov. 2021):

“The public health establishment made promises it could not keep. And when reality diverged from the script, they chose to deny, downplay, and demonize those who raised legitimate concerns.”

None of this meant the vaccines were worthless. They may have saved many lives among the elderly, the obese, and those with serious underlying conditions – which was obvious to anyone following the studies (like me) from the very first few months!

But they weren’t even remotely the miracle we were sold in late 2020. And worse – it was now clear that they came with serious and possibly life-threatening risks.

For people like me, who trusted the original promise, it was becoming harder and harder to square what we had been told with what we were now seeing.

The cracks weren’t just surface flaws anymore.

They were running deep.

Chapter 3. The Shift: From Science to Politics

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when COVID vaccination moved from being a scientific question to a political wedge. But sometime in the fall of 2021, it was pretty clear to me that vaccination status was no longer so much about public health, but about allegiance, morality, even virtue.

I admit, the early signals were not obvious – at least to those that were not habituated to following the story. When vaccines were first rolled out in Dec. 2020, the only dubious essays I was reading were coming from a handful of doctors and scientists I’d never heard of.

The CDC and other government agencies were holding fast to their original, pro-vaccine (and even pro-mandatory-vaccine) stance. And political leaders across the divide (except for Rand Paul) were united in encouraging people to get vaccinated.

Although it was clear to me that then-President Donald Trump was dubious about the severity of the COVID virus and the need for vaccines, he decided to get on board and put Operation Warp Speed into action, which did, indeed, fast-forward the production of the vaccines.

On Dec. 21, 2020, President-elect Joe Biden got his first jab of the vaccine on television, telling Americans, “There’s nothing to worry about.”

And Dr. Fauci, appearing alongside Biden, described the vaccines as “an historic scientific achievement.”

Notwithstanding my own doubts, I was hopeful that somehow this near unity on the necessity for widespread vaccination might transcend intense polarization that had already defined American life.

But that didn’t happen.

In March 2021, the Biden administration announced a national goal of vaccinating 70% of American adults by July 4.

Initially, the effort leaned on persuasion. But when it became clear that millions were hesitant – especially younger adults, minorities, and conservative rural populations – the tone began to harden.

Public health messaging started to frame vaccination not just as a smart choice, but as a moral obligation. People who expressed doubts were increasingly described as selfish, ignorant, or worse.

On July 16, 2021, President Biden announced that that “The only pandemic we have is among the unvaccinated.”

And Dr. Walensky magnified the sentiment with a statement that became a rallying call for pro-vaccine Americans:

“This is becoming a pandemic of the unvaccinated.”

The phrase was everywhere – on television, in newspapers, in online forums.

But it wasn’t accurate.

As early as May 2021, a study out of Israel had shown that vaccinated individuals could still contract and transmit the virus – particularly as the Delta variant spread.

Later studies, including a UK report from Public Health England (Aug. 6, 2021), confirmed that while vaccination reduced the risk of severe illness, it did not fully prevent transmission.

In other words, the vaccinated could still catch COVID – and still spread it to others.

But by then, the political momentum had already shifted too far.

Vaccine mandates began rolling out across the country.

On Sept. 9, 2021, President Biden announced sweeping new requirements:

* All businesses with 100 or more employees were required to “mandate” vaccines or weekly testing.

* Federal employees and contractors must be vaccinated, with no testing option.

* Healthcare workers in facilities receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding had to be vaccinated.

“We’ve been patient, but our patience is wearing thin,” Biden said in his announcement. “And your refusal has cost all of us.”

It was a remarkable moment.

The US government was now openly coercing private citizens to accept a medical intervention –or face loss of employment, income, and public standing.

At the same time, social pressure intensified.

Major corporations, universities, and sports leagues rushed to implement their own vaccine mandates. Airlines began requiring proof of vaccination for staff. Some cities, like New York and San Francisco, instituted vaccine passport systems for indoor dining, gyms, and theaters.

If you were unvaccinated, life became difficult – by design.

Mainstream media coverage reinforced the message. Unvaccinated individuals were routinely portrayed as reckless threats to public safety.

CNN anchor Don Lemon declared on Aug. 2, 2021: “Don’t have a vaccine? Don’t go to the hospital when you get sick.”

And MSNBC’s favorite birdbrain, Joy Reid, said on Aug. 23, 2021: “It’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks.”

The rhetoric expanded across most of the developed world. In Jan. 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron proudly stated, “I really want to piss off the unvaccinated.”

Critics of this approach warned that turning public health into a political weapon would backfire.

Dr. Jay Bhattacharya wrote (Oct. 2021):

“Public health depends on trust. Once you politicize it, you lose that trust – and it’s very hard to get it back.”

And for a time, the strategy seemed to work. Vaccination rates rose. Corporations, government agencies, and universities all reported higher compliance after mandates were put in place.

But something deeper was happening too.

The definition of “vaccinated” began to shift.

Originally, it meant two doses of Pfizer or Moderna or one dose of Johnson & Johnson.

But by late 2021, as booster campaigns ramped up, officials suggested that “fully vaccinated” would soon mean three shots.

Dr. Fauci said in an interview on CNN (Nov. 21, 2021):

“I would not be surprised at all if ‘fully vaccinated’ will mean three doses.”

This moving target frustrated many who had gotten vaccinated in good faith – and alarmed those who had complied only under pressure.

Meanwhile, censorship of dissenting views accelerated.

Social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube cracked down on vaccine-related “misinformation.”

Sometimes that meant removing obvious falsehoods. But often it meant suppressing legitimate debates – about vaccine mandates, side effects, natural immunity, and policy trade-offs.

For example:

* In July 2021, YouTube removed videos from Sen. Rand Paul questioning the effectiveness of cloth masks.

* In Oct. 2021, Twitter suspended the account of Dr. Robert Malone, one of the early pioneers of mRNA vaccine technology, after he raised concerns about risks associated with the COVID vaccines.

The message was clear: Disagreement, even from credentialed scientists and physicians, would not be tolerated.

I was listening to this and thinking, “Isn’t the core of science open inquiry? Asking questions – including unpopular ones – and then doing reliable tests to answer them?”

In the rush to promote vaccination, officials and media figures often portrayed any questioning of vaccine policy as anti-science, anti-vaccine, or even anti-American.

But the issues were far more nuanced.

By that time a sizeable contrarian conversation had begun among the skeptics and even among the moderates. They were asking what seemed to me very reasonable questions:

* How long does vaccine-induced immunity last?

* What are the real risks of myocarditis for young men?

* Should natural immunity from prior infection be considered equivalent to vaccination?

* How much should individual risk profiles shape vaccine recommendations?

But instead of treating them scientifically, the establishment was refuting them out of hand. These were conspiracy theories, they were saying.

And it wasn’t just establishment figures. It was now the argument of half the country. This critically important scientific issue had become almost entirely political. It was furthering the divide not just among scientists and doctors, but among ordinary Americans – even within friendship groups and families.

Chapter 4. Emerging Evidence: Safety Signals and Scientific Dissent

While the public messaging around COVID vaccines continued to insist that they were not just safe and effective but essential, the evidence against it within the scientific and medical communities was piling up.

Myocarditis and Pericarditis

The first major red flag was myocarditis.

By June 2021, the CDC had confirmed an elevated risk of myocarditis and pericarditis – especially among young males aged 16 to 24 – following the second dose of mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna).

The advisory panel’s June 23 meeting laid out the numbers plainly:

* Among males aged 12 to 17, there were 62.8 cases per million second doses – far higher than expected background rates.

* For males aged 18 to 24, the rate was slightly lower but still concerning: 50.5 cases per million.

These numbers came from CDC’s own Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) and later confirmed through more detailed studies. Dr. Tom Shimabukuro, head of the CDC’s vaccine safety team, admitted that “There does appear to be a likely association of myocarditis with mRNA vaccination.”

Young men who developed chest pain, difficulty breathing, or palpitations were advised to seek immediate medical attention – but the official narrative was that incidents of myocarditis and pericarditis were rare and mild.

This was a lie. And every cardiologist knew it. Or should have known it. But 95% of the Health Industrial Complex and most journalists reporting on health hardly mentioned it. And when they did, they echoed the lie.

There were a few brave exceptions.

In the June 2021 issue of MedPage Today, Dr. Vinay Prasad wrote:

“Myocarditis is not always benign. There are long-term risks, including arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. We need honest risk-benefit discussions, especially for low-risk groups like adolescents.”

In August that year, a study published in JAMA Cardiology found that myocarditis after mRNA vaccination had a median onset of just two to three days post-injection, with clinical presentations ranging from chest pain to heart failure symptoms. And that MRI scans often revealed lasting inflammation weeks after hospitalization.

Still, the CDC and FDA continued to publicly pronounce the vaccines as safe and effective. (For the most part, they still do today!)

Blood-Clotting Disorders

Reports on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine (and AstraZeneca’s vaccine abroad) raised a different concern – blood-clotting disorders.

And then came credible reports of “cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) combined with low platelet counts – a condition later labeled Vaccine-Induced Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia (VITT).

And a few weeks earlier, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) identified a similar pattern with the AstraZeneca vaccine.

Ultimately, the regulators acknowledged a causal link between adenoviral vector vaccines and clotting disorders – particularly in women under 50.

The risk was small – estimated around 7 cases per million vaccinations – but it wasn’t nonexistent.

By Dec. 2021, the CDC recommended that Americans opt for mRNA vaccines (Pfizer or Moderna) over Johnson & Johnson whenever possible – a quiet admission that not all vaccines carried the same safety profile.

VAERS Data and Underreporting Concerns

Meanwhile, the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) – a database co-managed by the CDC and FDA – began accumulating an unprecedented number of negative reports on the after-effects of the vaccines.

In fact, by mid-2021, VAERS had received over 400,000 reports related to COVID vaccines, including deaths, hospitalizations, and serious adverse events. And by the end of 2021, that number would rise to more than 700,000.

Note: It’s important to understand that VAERS reports are not proof of causality. Anyone can submit a report. Some reports are incomplete or unverified. But historically, VAERS has been viewed as a useful early warning system for potential safety signals.

Critics such as Dr. Peter McCullough, an internist and cardiologist, argued that the sheer volume and nature of the reports should have triggered more formal investigations. In a presentation to the Texas Senate Health and Human Services Committee (June 27, 2021), McCullough stated:

“In the past, when we had fifty unexplained deaths following a vaccine, we would pull it off the market. Here, we have thousands.”

Note: The actual numbers of negative reports were probably much higher. That’s because VAERS had traditionally suffered from systematic underreporting.

A famous 2010 report commissioned by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and conducted by Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare found that “Fewer than 1% of vaccine adverse events are reported to VAERS.”

As the number of vaccine skeptics grew, so did efforts by the government, the Dems, and the Health Industrial Complex to discredit them as “conspiracy theorists.”

Some examples:

* Dr. Robert Malone, a pioneer of mRNA technology, was banned from Twitter in Dec. 2021 after questioning vaccine safety and efficacy.

* Dr. Jessica Rose, a Canadian immunologist who published analyses of VAERS data showing elevated risks of myocarditis, found her work removed from preprint servers and rejected by mainstream journals.

* The Great Barrington Declaration authors – Dr. Jay Bhattacharya (Stanford), Dr. Sunetra Gupta (Oxford), and Dr. Martin Kulldorff (Harvard) – who had earlier criticized lockdown policies, were increasingly lumped into the “misinformation” category despite impressive academic credentials.

Rather than engage with these critics in open debate, public health institutions – and many media outlets – chose to silence or sideline them.

Dr. Bhattacharya later described it this way in an interview with The Epoch Times (Feb. 2022): “They decided that it was better to manipulate public opinion than to have an honest scientific discussion.”

What’s Worse

It was bad enough that the government and the mainstream media were selling a narrative that was largely untrue, but they then began promoting the completely absurd idea that the administration of vaccines should include large portions of the population for whom contracting the virus was no more dangerous than getting the flu.

By this time, it was already widely accepted that the virus was seriously dangerous to only two segments of the American population: very old people and obese people suffering from comorbidities (primarily diabetes).

I remember writing about this back then. There were already charts available that provided the lethality of the virus by age and sex. And it was clear that healthy people – even middle-aged people – had very little risk of getting very sick, and younger people (younger than 30) had virtually zero risk.

Yet the advice coming out of the CDC and NIH was for every age group, every health status.

By late 2021, the evidence pointed to a reality that was very different from the mainstream narrative.

We knew back then that the vaccines were responsible for elevated risks of myocarditis for young men and rare but nonetheless serious clotting disorders.

Furthermore, there was a growing suspicion among vaccine skeptic researchers that they were also responsible for many other heart-related illnesses and even something they were calling “turbo” cancers. (Cancers appearing at late stages among healthy young people.)

It was a binary of bad factors:

* A surveillance system showing an unprecedented volume of adverse event reports, and…

* The suppression of scientific dissent and open debate.

Here’s the thing that bothers me. It would have been very easy for government health officials to adjust their messaging. They could have acknowledged the complexities. They could have treated adults like adults – capable of weighing benefits and risks based on their individual situations.

Instead, they doubled down on their promotions and policies.