Putting My Editor’s Hat Back On…

I have spent a fair amount of time in my publishing career training, coaching, and editing new and developing writers. It’s an aspect of my work-life I very much enjoy because it is an intimate and earnest form of teaching. And it has pragmatic benefits, as well. If I do a good job, the writer becomes a stronger writer. As a stronger writer, he wins a larger and more loyal base of readers. As his readership grows, so do the revenues of our business. And that gives our readers a better product, our company larger revenues, and the person I’m coaching a more successful and lucrative career.

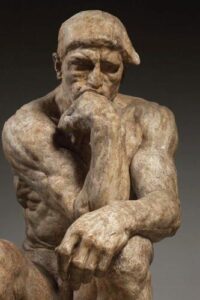

Philosophically, what I’m doing provides all three of life’s sustaining pleasures: I’m working productively on something I feel is important. He’s learning something that he thinks is important. And both of us are sharing important knowledge.

In less self-elevating terms, I like it because I’m confident I can do it well and because what I’m doing is appreciated by the person I’m coaching.

That’s all good and true for coaching new and developing writers. But what about a writer who has serious writing credentials? What about coaching a writer that, from an objective perspective, has all (or more) of the professional chops that I have? It can be intimidating!

I’m doing that now. I’ve been working with a very accomplished writer of newspaper and magazine essays and several bestselling books. He’s got more writing medals on his chest than I could claim, but he’s new to the sort of writing we do at Agora: newsletters.

Newsletter writing differs from other kinds in the two ways contained in the word “newsletter.” It is meant to convey some useful insight on economic and investment developments (news). And it is meant to do so in an informal and almost intimate manner (letter).

This particular writer is an expert in his subject matter: investing. In terms of knowledge of that field, he’s way ahead of me. He’s also very good at structuring an argument, telling a story, writing with personality, etc.

So, you would think that there is practically nothing I can teach him. Nothing I can do to help him advance in his new job as a newsletter writer. I wondered about that when I agreed to coach him. And yet, the relationship seems to be working. I’m quite confident that I’m making his writing better!

The icing on the cake is that we are both enjoying the process. As it turns out, as good a writer as he is, he recognizes the value in what I’m teaching him – the nuances that make newsletter writing unique and uniquely valuable to newsletter readers. And that fact makes my job so much easier. He “gets” my comments immediately and puts them into practice as well as (and sometimes better than) I could hope for.

Part of me fears that, in another month or so, I’ll have nothing left to give him. But I know that’s not true. I know, from this experience and from others, that a good writer – even a great writer – will almost always write better with a good editor.

Think about it. Almost every great writer I can think of had editors that greatly improved their work. And not just in the beginning. Throughout their careers. A few examples:

* Max Perkins and Thomas Wolfe

* Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot

* Max Brod and Franz Kafka

* Michael Pietsch and David Foster Wallace