Search results

54 results found.

54 results found.

“Do not say little in many words but a great deal in a few.” – Pythagoras

6 Cuss Words I’m Trying to Include in My Conversations

I must be going through some sort of nostalgia phase. I’m watching old movies, rereading books I read when I was young, and studying history.

Recently, I came across a list of antiquated cuss words that made me wish I was living back when I could work them into my conversations. Maybe I still can!

Here are six (from Merriam-Webster) for your consideration:

Thunderation has gone through some evolution as a swear word. It’s a lighter, more appropriate version of “tarnation,” which is in turn a lightening of “damnation.” This term came to popularity in the 1850s and faded in the late 1950s. And it should come back. It can be used in the same way as “Hell!” or “Damn!” Example: “Thunderation, that’s a strong horse! You can barely control it!”

Much in the same way as thunderation, swounds is a proper swear word. It’s a shortening of “God’s wounds,” a common oath used in the Middle Ages that refers to the wounds in Christ’s crucifixion. There are a number of similar terms, such as “strewth,” which means God’s strength. Example: “Swounds! What a horrible accident!”

Cockney slang is a very specific style of speech native to England. London, in particular. By creating rhyming phrases, speakers of Cockney slang had a unique vocabulary that almost operated as a secret code. “Bloody Nora” is an example of such slang – a stand-in for “flaming horror.” It can be used as a description, such as, “You look like a Bloody Nora!” Although this is best done with your worst/best Michael Caine impression to really sell it.

During the medieval period, “sard” was a popular alternative for, we’ll call it, “seducing a woman.” It phased out in the 1600s, and hasn’t been used since. But it flows off the tongue well and doesn’t sound as vulgar as some modern-day alternatives. Example: “I’m going to sard her and even stay for breakfast afterwards.”

Quim actually had a very short resurgence in 2012, when the first Avengers movie came out. Loki, the villain of the movie, calls Black Widow a “mewling quim” in order to shock and insult her into giving him information. It ultimately doesn’t work, but it brought “quim” to the public consciousness, where it hadn’t been for a long time. “Quim” refers to the female anatomy, and is one of the more insulting ways to refer to it. It’s not a term that should be used lightly, but as a more archaic insult, it has value.

Fustilarian is a Shakespearean word, and is a beautiful way to insult someone (especially when they don’t know what it means). The word was first used by Shakespeare in Henry IV in a string of insults by Falstaff to a woman who is on the scene when he is arrested: “Away, you scullion, you rampallion, you fustilarian! I’ll tickle your catastrophe.”

Fustilarious is an adjective meaning low/common and foul smelling. When you call someone a fustilarian, you’re calling him a low fellow, and a stinky one to boot. The word is very rare, passing out of fashion almost as soon as it was coined… which means it’s prime for a comeback.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“Intelligence without ambition is a bird without wings.” – Salvador Dali

10 Ways to Get Rich as an Employee

Most people know me as an entrepreneur, a person that has started and/or consulted with dozens of successful multimillion-dollar entrepreneurial businesses, and the author of Ready, Fire, Aim, a NYT bestselling book on entrepreneurship.

In fact, I made my first 10 million as an intrapreneur – an employee that became a partner in a business that went from $1 million to $135 million in about seven years. I did that by doing everything I’m about to tell you…

1. Begin well.

Recognize a simple truth: If your ambition is to go as far as you can go as an employee, you have to accept the fact that you have to distinguish yourself as a superstar. That means you have to be willing to do more, learn more, and care more than your peers. This won’t increase your general happiness in life, but it will give you the opportunity to have more freedom, authority, and autonomy. Plus you will make a whole lot more money.

2. Set the only goal that makes sense.

On day one of your new job, set this goal: to become the CEO of the company. It doesn’t even matter if that’s really not your goal. Anything and everything you can get from your current job will come faster and easier if you assign yourself this crazy goal of becoming the CEO.

3. Study the architecture.

It’s amazing how many people come to work each day with little to no idea of what their business does or how it does it. They enter data or process accounts payable or write computer code without any knowledge of or interest in how the company works.

Remember: The goal you’ve assigned yourself is to become CEO. That means you must take the time to educate yourself about the structure, the key people, and the basic operations of the business. Read company literature. Interview your boss and other bosses. Talk to your fellow employees.

4. Take names.

Walk around. Make eye contact and smile. As you expand your knowledge of the business and its functions, get to know some of the people outside your immediate work environment. Your goal is not to make friends, but to create a network of people that can help you have a bigger and more meaningful impact on the growth of the company.

5. Use your brain.

You can’t always be the smartest person in the room, but you should seek to be. Pay attention. Ask questions when you don’t understand. Take notes. Study. Be determined to know the business inside and out. This will mean extra work, evenings and weekends. It will be a good investment of your time.

6. Catch the worm.

Don’t believe anyone that tells you it’s quality, not quantity, that counts. Both are important. That applies to every aspect of your work performance, including the hours you work. To get on the fast track in a new company, you must not only work at least 10 hours a day, at least one of those hours should be in your office before your boss arrives. Being willing to work late shows loyalty and commitment. Arriving early shows initiative and ambition.

7. Make your first fan.

Your fate during the early days of your employment is dependent on your boss’s opinion of you. So, make it your first priority to figure him out and become the employee he wants you to be.

8. Be thankful and thoughtful.

Every time someone helps you, teaches your something, or does you a favor – even a small one – send them a personalized thank-you of some sort. In some cases, an email will suffice. In other cases, a handwritten note would be better. The point is to let people know that you are open to, and grateful for, advice and encouragement.

9. Step up.

When something bad happens under your watch, don’t make excuses. If it’s your fault, fess up immediately. If it isn’t your fault, don’t play the blame game. Explain what happened, but also take responsibility for it. You want to be known as someone that can be relied on to solve problems, not just point fingers.

10. Get ready for a promotion.

What is the job you should do next? The one that will advance you fastest? You should always have your eye on a position with more responsibility and authority. And usually, that means a job that can make the company more bottom-line dollars.

Think about what that job can be and then start spending your free time hanging out with the people that are currently doing it. Learn everything they know. Help them solve their problems. Become their fervent apprentice. And when a job in their department opens up, they will think of you… and you will be fully prepared to jump on it.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“History is philosophy teaching by example.” – Thucydides

Western Culture in One Lesson, Part I

Today, let’s talk about this idea of Western Civilization. The idea that America and Western Europe share a common culture that dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. And that this culture is the bedrock that has supported the accomplishments of the West for the last 2600 years.

When I was a kid, it was an accepted fact.

Now, it’s debatable. The ties that bound us together have unwound. Our core values are being called into question. We no longer see ourselves as Westerners in the European tradition. Instead, we are members of political or identity groups – each with its own views – that are fighting with one another like warring tribes.

This is destructive. It’s also not true. Even a cursory review of the institutions and conventions we take for granted – government, democracy, liberty, privacy, the sovereign individual, and economics, among other things – would make it clear that we share much more with the rest of the Western world than we don’t. And that more than 90% of what we value can be traced back to a common source: the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome.

All of the following fields of human knowledge are rooted in Greek and Roman thinking.

* Logic and Reason: first, the Milesian School (circa 600 BC), which gave rise to the scientific method; then, and most influentially, Aristotle (384 BC to 322 BC)

* Mathematics: Pythagoras (582 BC to 507 BC) and Euclid (325 BC to 265 BC)

* Physics: Empedocles (495 BC to 435 BC) and Democritus (460 BC to 370 BC); then Aristotle.

* Ethics: Aristotle and Plato (469 BC to 399 BC)

* Individuality and Idealism: Plato

* Astronomy: Aristarchus (325 BC to 250 BC)

* Geography and Paleontology: Xenophanes (570 BC to 475 BC)

* Stoicism: Zeno (340 BC to 226 BC), Epictetus (50 AD to 138 AD), and Marcus Aurelius (121 AD to 180 AD)

* Medicine: Hippocrates (460 BC to 370 BC)

* Skepticism and Relativism: Protagoras (490 BC to 421 BC), the Sophists (5th and 4th centuries BC), and Pyrrho of Elis (365 BC to 275 BC)

* Politics: Aristotle and Plato

There is a good explanation for this. Before Greece and Rome, primitive religions determined the answers to life’s most important questions – everything from how the world works to how one should conduct oneself.

But ancient Greece didn’t have a state religion. It wasn’t even a sovereign nation. It was a collection of city states, each with its own ideas about ethics, politics, and so on. And when Rome conquered Greece, as Herodotus tells us in TheHistories (430 BC), it adopted Greek culture.

As a result, instead of looking to religion for answers to their questions, the citizens of Greece and Rome began to discuss these issues amongst themselves. And by doing so, they developed what could be called the core curriculum of Western Civilization.

By the way, this curriculum includes much more than the scientific and philosophical categories listed above. The ancient Greeks and Romans also initiated and incorporated into their cultures such big ideas as free trade, currency, democracy, anti-tyranny (Cato 95 BC to 46 BC), duty to country, family values, law (“innocent until proven guilty”), and public service, to name a few.

So don’t tell me there is no such thing as Western Civilization or that Americans and Europeans are not connected to one another by a common intellectual history.

There have been significant contributions to philosophy, politics, and science that came from outside the Western cannon. But not many. It seems to me, from the reading I’ve done (see “Worth Reading,” below), that 90% of the best and most useful ideas were figured out at least two thousand years ago.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

In the mid 1990s, when I began consulting with Agora, the business had its headquarters in a mostly black Baltimore neighborhood. It was about a mile from the inner harbor, where I had an apartment on the sixth floor of a new, rather luxurious, building. On pleasant days, I’d walk to work, always stopping for breakfast at a little market about a block from my office that was run by a family of Koreans.

There was nothing about the place that was exceptional. The lighting was poor and the aisles were narrow. But the shelves were overflowing with every sort of consumable you could possibly need. And it had a counter that was just long enough to accommodate four stools. The only way you could not have a clear picture of what I’m describing is if you have never been to any large- or mid-sized city in the USA.

The family that owned it – the parents must have been in their late fifties – had three teenage daughters. The parents worked from opening to closing. The girls worked after school and on weekends. They were not, by American standards, friendly. But because I wanted to get to know them a little, I gradually and gently pushed against their modest formality.

The parents were immigrants. They spoke just enough English to communicate with their customers. The children had been born in the US. They were intelligent, hardworking, and extraordinarily respectful of their parents. All three of them were accepted – on scholarship – into good local colleges. The family was, in other words, an Asian-American cliché.

What struck me at the time was how the family managed the girls’ education. While the eldest was in college, the other two continued working at the family business. When the eldest graduated, she went back to work and the second daughter went to college. When the second daughter graduated, she went back to work and the third daughter went to college.

I asked the girls if they thought it was fair – if they thought they should have been able to go off and start their own careers (and lives) once they had a diploma. They had no idea what I was talking about. My question made no sense to them.

Asians in America, Part II:

Why Are They So Successful?

“Immigrants have been coming to our shores for generations to live the dream that is America. [We] have seen time and again that that dream is achievable.” – Nikki Haley

On Monday, I talked about the amazing success Asian immigrants have had in America. In terms of wealth, health, education, and optimism, they outrank every other racial group, including White Americans.

Why is that? Why is it that Asian-Americans, themselves victims of bias and discrimination, have achieved so much?

One factor may be that so many of them are first- and second-generation immigrants. There is a theory that immigrants are by nature an above-average group – more ambitious and enterprising than their countrymen that choose to stay home. So this could well be a key reason why Asians have done so well in the US.

But there are other reasons, too. If you spend even a single day researching Asians in America, you will discover that, despite the differences among them, they share some cultural characteristics. Specifically, they have a belief in and a commitment to:

Hard Work

Asian-Americans have a pervasive belief in the rewards of hard work. In a recent poll, 69% said they believed that “anyone can get ahead if he or she is willing to work hard.” More importantly, 93% described themselves and members of their country of origin as “very hard working.”

But do Asian-Americans actually outwork other races?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Asian-Americans work about the same number of hours as every other racial group. Here is the data:

* White Americans – 38.9 hours per week (on average)

* African-Americans – 38.7 hours per week

* Asian-Americans – 38.9 hours per week

* Hispanic-Americans – 38.2 hours per week

As you can see, the differences in terms of hours worked are very small.

But as I said on Monday, there are some stark differences when you look at unemployment figures. Asian-Americans – at an astonishing 3% – have the lowest unemployment rate of any racial group.

That could indicate not just a commitment to work but also a shame in not working – two very different values.

Education

Asian-Americans place a high value on education. And they work as hard as, or harder than, any other racial or ethnic group in America at educating themselves and their children.

As I pointed out on Monday:

* 87% of Asians aged 25 and older are high school graduates.

* 53% have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

* 23.6% have a graduate or professional degree.

And they’re great students.

There have been many studies done on why Asian-Americans do so well in school.

In one, a meta study of two national surveys that followed about 5000 students from kindergarten through high school, researchers were looking for evidence to explain the superior academic performance of the Asian-Americans. They had theorized that it had something to do with their innate cognitive ability – but that’s not what they found. Instead, it seemed to be due to a high-effort mentality instilled in the children by their parents. Asian-Americans, the researchers said, view education as a primary means for upward mobility – and they exert considerable pressure on their children to succeed.

Family Values

Compared to other racial groups, Asian-Americans place a higher value on family, marriage, and parental fealty.

Consider this:

* According to a Pew Research Center study, the majority of Asian-American adults list having a successful marriage and being a good parent as two of the most important things in life.

* Asian-Americans are more likely than other racial groups to live in a multi-generational household. Some 28% live with at least two adult generations under the same roof.

* 84% of Asian-American children (17 or younger) belong to a household with two parents. This compares to 68% of all American children. And only 16% of Asian-American newborns have an unmarried mother, compared to the national average of 40%.

* Asian-Americans have a strong sense of respect for their parents. About two-thirds say that parents should have a lot of or some influence in choosing their children’s profession (66%) and spouse (61%).

This is at least partly influenced by philosophical and religious teachings. Filial piety is an important element in Buddhism, Korean Confucianism, Taoism, and in Japanese and Vietnamese cultures.

* And here’s something I found noteworthy: In a recent study, 62% of Asians said that they believe American parents do not pressure their children enough.

Hard to Argue

Those are the facts.

What’s interesting is that this amazing story of Asian-American success in the US is not being told and celebrated. It is being ignored and even disputed because it suggests that a major thesis of identity theorists – that systemic racism is the cause of income, wealth, and education inequality in America – may be wrong. It also suggest that the solution to financial, social, and educational inequalities may not be as easy as making political, regulatory, or economic changes.

I’ll come back to this and related “identity” questions in future essays.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“Every step of life shows much caution is required.”

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

When I’m Going to Get Back Into Stocks

The Dow has fallen.

A reader asks: Is it time to get back into stocks?

I’m not an investment advisor. I don’t feel comfortable telling others what to do with their money. I prefer to say what I’m doing and why, and then let my readers decide if it makes sense for them.

So: Am I getting back into stocks? Not now. I’ll tell you why.

We just went through one of the longest and largest bull markets in my lifetime. From March 9, 2009 to March 11, 2020, the Dow and S&P 500 rose 351% and 400%, respectively. That was a fun ride – and I’m glad I was on it. But it became clearer and clearer as time passed that the bull I was riding was getting old.

The day the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic, the market tumbled 6%. It has fallen since then, and is currently down about 25% from its high. (Erasing more than $8 trillion of the US market capitalization.)

When deciding to buy a stock, there are two simple ways I judge its value. The first, which I’ve been doing forever, is the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E). That is determined by dividing the stock price by the earnings per share. (If the price of stock X is $50, and the earnings per share is 5, the P/E is 10.)

There are other ways to measure share value. A popular one is the price-to-sales ratio. It is determined by dividing a company’s market cap (the total value of outstanding shares) by its revenue. This is a good quick way to compare prices of companies within a given industry, but it doesn’t make sense to value stocks across the board. Another metric is the price-to-book ratio. A business’s book value is determined by subtracting its liabilities from its assets. You take that book value and divide it by the number of outstanding shares, which gives you the book value per share. Then you divide the share price by the book value per share. I don’t use this method because it’s just too much work for my purposes.

What I like about the P/E is that it corresponds to the way I value private businesses. I wouldn’t be interested in buying a company based on sales. And I certainly wouldn’t value it that way. I’m interested in profits. Earnings are profits. The other thing I like about the P/E is that, because it values the shares on profits, it can be used to fairly value large, established businesses in most industries – from manufacturing to agriculture to communications to energy, and so on. In other words, it’s useful for valuing the sort of stocks I want to own: large-cap, dividend-giving, industry-dominating companies that have a long history of profitability and are likely to be here far into the future.

If I traded stocks or invested in growth stocks, I’m sure I’d be interested in getting more sophisticated with my value calculations. But my strategy for stocks is based on my confidence that I do not and will not ever have the interest in or patience for beating long-term market averages. I’m happy to get 8% to 12% on my money over the long haul.

Today, the average P/E for the Dow is 16.4. That’s down two points from a year ago, and it’s getting very close to the historical average of 16. P/E ratios are not reliable predictors of short-term market moves, but over 10 years or more, they work pretty well. Thus, buying stocks with P/E ratios of 15 or less would make sense. And many value investors use that as a buy-in signal.

As an investor in private businesses, I have never paid anywhere near 15 times earnings. For newer, growing businesses, I’ve paid up to 10 times earnings. But for larger, established businesses in my industry, the range is usually a 4 to 6 times multiple of the average earnings over the prior three years.

In other words, for a business that made profits of $80,000, $100,000, and $120,000 over the prior three years (an average of $100,000 per year), I’d be willing to pay up to $600,000.

You can’t do that with larger, stable public companies. Priced at the historic P/E of 16, I’d have to pay $1.5 million for the same company.

The reason for this is supply and demand. In the public sector, there are billions of dollars of buying demand every day. The larger, institutional buyers are happy to pay 16 times earnings for the sort of stocks I prefer to buy. And they usually will. So for me, I’m motivated to buy these stocks in the 12 to 14 P/E range.

Recently, I’ve added a second tool to my valuation kit. I’m not exactly sure how I will use it, but I’m looking at it because I think it makes sense.

It’s called the Dow-to-Gold ratio. I learned about it from Bill Bonner, the founder of Agora, and Tom Dyson, who helped me assemble the core holdings of the stock portfolio I have now.

Here’s how Tom described this tool:

It’s NOT a speculation in gold. It’s a long-term buy-and-hold stock market investment strategy… with a simple market-timing element that helps us buy low and sell high.

Most of the time, we hold the stock of the world’s best dividend-raising companies. We call these “dividend aristocrats” – companies like McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Hershey’s, P&G, J&J ,and Phillip Morris. [Note: This is basically the same core group that I have in Legacy stocks. No surprise there, since Tom helped design the Legacy Portfolio.]

Some of the time – when these stocks get too overbought and expensive – we go to the sidelines in gold.

We never cash out. And we never hold anything except gold and dividend aristocrats. We just wait for the Dow-to-Gold ratio to reach extremes… and then we rotate between stocks and gold accordingly.

As such, the Dow-to-Gold ratio is the only number that matters to us.

For Bill and Tom, the Dow-to-Gold buy-in ratio is 5. When they can buy all the Dow stocks for five times the value of an ounce of gold, they will be all in.

Right now, the ratio is well above 5. But it’s moving down with stock prices down and gold moving up. It’s likely that gold will move up considerably more if the economy doesn’t drastically improve by mid-summer. If that’s the case, we will see the Dow-to-Gold ratio moving towards 5.

But I’m not going to wait that long. As I said, this is a new metric for me. It makes the most sense in the long view. As individual stocks that I favor move towards a P/E of 12 and the Dow-to-Gold ratio continues to drop, I’ll start buying.

But on an individual basis.

In the meantime, I’ll keep my money in cash and wait to see what happens.

PS: I may put a very small portion of that cash to speculate. If I do, I’ll let you know.

“A sense of purpose is both the fuel and the compass one needs to move through confusion.” – Michael Masterson

Not every successful person sets yearly goals at the New Year. Just 90% do.

If you are among the 10% that can achieve your objectives without formalizing them – without writing them down and tracking them – you have every right to look down your nose at the rest of us that rely on goal setting to get things done.

How can you tell if you are one of the superior 10%?

Simply look back on the past year… and the past 5 years… and ask yourself if you have accomplished everything you wanted to accomplish.

If you haven’t, you are one of us.

I have written dozens of essays and almost as many book chapters on the subject. If you’ve read them, you know that my goal setting system, the one I’ve been refining for more than 30 years, departs from conventional wisdom in several respects.

* I do not believe in setting highly specific annual goals.

* I don’t believe in “stretch” goals.

* And I don’t believe in emotionally attaching myself to my goals.

One of the common recommendations I do practice is to publish my goals. Not because I want someone else to hold me accountable, but because I want to be able to hold myself accountable.

So that’s what this is: a public posting of my primary goals for 2020.

New Year Resolutions: 35 Ways I’m Going to Do More and Be More in 2020

Social Goals

Personal Projects

Business and Wealth Building Objectives

Health Goals

Stoic Goal

Own my self-worth. Do not burden others with the responsibility to maintain my self-esteem.

Zen Goal

Work with intentionality on all my goals without caring about accomplishing any of them. As I said in my January 1 blog: “You can learn to act intentionally without attachment. Remember, the way is the true goal. And movement is the reward.”

“An idea, like a ghost, must be spoken to a little before it will explain itself.”

– Charles Dickens

The Big Idea: The Biggest Misconception in Marketing

Is there a marketing concept more misunderstood than the “Big Idea”?

Ever since The Agora became the dominant direct response publisher in the world, the term has become synonymous with breakthrough marketing packages. That’s because The Agora has long been associated with “Big Idea” promotions.

But what, exactly, is a Big Idea? Ask one expert and he’ll say it’s a big promise. Ask another and she’ll say it’s a big and clever lead. Ask a third and he’ll say it’s the idea behind a package that crushes the control.

This confusion is rampant across the marketing world. Even within The Agora companies, many marketers and copywriters use “Big Idea” to mean different things.

It was David Ogilvy, I believe, who coined and popularized the term. What’s interesting is that for Ogilvy a Big Idea wasn’t actually an idea at all. It was something else entirely.

He used “Big Idea” to describe what he was doing in the field of general advertising: magazine campaigns. His ads usually consisted of a photo (or drawing) and a phrase. The image provoked an inspirational emotion. The associated phrase made the connection between that inspiration and the product. Memorable examples include The Marlboro Man and The Man in the Hathaway Shirt.

Ogilvy’s Big Idea ads were not about better mileage or faster service or saving money. They were about notions and hopes and dreams. For him, Big Ideas were about what I call “deeper benefits” – psychological benefits, such as affirmation and self-esteem. (“If I smoke Marlboros, women might find me manlier. And if women find me manlier, they will like me more. And if they like me more, I will feel better about myself as a man.”) They did not convey literal benefits of any kind.

This is a very important distinction – and a critical one, because it reflects the essential difference between general and direct response advertising. The primary goal of general advertising is to create brand recognition. The primary goal of direct response is to elicit an immediate response (usually, a sale). The first relies heavily on images. The second almost entirely on language.

This is not to say that language did not (or does not) play a role in general advertising. Before Ogilvy, there were many successful general advertising campaigns that relied primarily on language. But these tended to focus on a USP, such as how smooth and quiet the car’s engine might be. An image was usually present, but it was there primarily to support the USP or simply showcase the product. It wasn’t expected to carry much weight.

Ogilvy’s Big Idea campaigns were, as I said, short on words and big on imagery. And when they worked, it was the imagery that did the heavy lifting.

His understanding of imagery was brilliant and enormously successful. The Big Idea became the standard for what a great brand advertising campaign could be. And it still is today.

But in the 1980s, on the other side of the advertising pond in the world of direct marketing, the Big Idea was being used to describe an entirely different approach. Bill Bonner was having great success writing direct mail packages to sell investment newsletters. And he was doing so by writing long letters explaining what was wrong with the economy and how those problems were going to radically change the investment landscape.

Nobody was writing promotions like that at the time. Everyone was writing packages about how much money one could make by investing in gold or in a particular group of stocks.

Bill’s sales copy was short on promises and offers but big on ideas. Ideas such as: Government debt will lead to a massive recession. Or: Inflammation is the cause of all modern illnesses. His interest in those ideas was the basis of a new kind of marketing strategy. And he used Ogilvy’s term for it because it accurately described what he was doing.

Bill began his sales letters with an indirect lead – writing not about the product but about an idea that might seem at first unrelated to the product. By doing this, Bill believed, the customer would be less resistant to the sales pitch itself and more open to thinking about problems that might get him into a frame of mind (and heart) where the product might suggest itself as a natural solution.

When I started working with Bill at Agora in the mid 1990s, we began the first training program in our industry in copywriting. I had brought with me a lot of ideas about how to best write direct sales letters – not just promise-oriented pitches but offer-driven campaigns and invitations, too.

Together, we taught the full range – from the most direct leads (offers) to the least (stories). We met every day for about a year with a dozen fledgling writers, many of whom went on to have very successful careers. And we continued to develop ideas about effective copy and how to teach it for many more years.

During all that time, the status of the Big Idea as a marketing “secret” never lost its appeal. People still talked about it, wrote essays on it, lectured on it, and so on. But the definition was becoming more and more diverse.

Nowadays, the “Big Idea” retains neither David Ogilvy’s original meaning nor Bill Bonner’s reinvention of it. For most people, it simply refers to a sales campaign that works really well – i.e., one that gets a very strong response.

This is unfortunate for two reasons: It renders the term meaninglessness, and it deprives young copywriters of an understanding of the concepts behind both Ogilvy’s and Bill’s thinking.

For Ogilvy, a Big Idea was an evocative image that could be connected with a psychological benefit. For Bill, it was an actual big (i.e., important) idea that had or could have significant consequences for the prospect.

But what a Big Idea is not(and this perhaps is the key thing I’m trying to convey here) is a strong promise or a clever offer or a captivating story – or any of the other things marketers do to stimulate sales. A Big Idea in direct marketing can only be an intellectually and emotionally compelling idea.

Offering a quick and easy solution to a problem… introducing a startling fact… making a convincing argument… these are all very solid ways to structure a sales pitch. And if you asked me to do the arithmetic, I’d guess that they account for more than 80% of the successful sales campaigns that are out there today. I can tell youfor certain that The Agora has sold more subscriptions with direct leads that featured promises than it has with indirect ones that presented Big Ideas.

That said, when they work, Big Idea packages can be game changers. A single campaign can literally double the size of your business.

So how do you write one? I’ll tell you in my next essay…

rampant (adjective)

When you describe something as rampant (RAM-punt), you mean that it is not only common, it is getting worse in an uncontrolled way. As I used it today: “[Confusion about what is meant by the ‘Big Idea’] is rampant across the marketing world. Even within The Agora companies, many marketers and copywriters use ‘Big Idea’ to mean different things.”

What I Learned About Love

Once a month, I spend an hour talking to BK about success in life and business.

He usually begins the conversation with a question about some business-related issue he’s been thinking about. It’s always a good, nuanced question that sparks the ensuing discussion. In our first few sessions, he did most of the asking and I was the guy with the answers.

During our most recent phone call, we touched on many topics – including the history of The Agora and my newly baked theory on how ingrained personality traits determine the potential and contributions of individual employees. And then somehow – I can’t remember how it happened – the conversation turned to love. Or rather the expression of love.

BK mentioned a book I had not read called The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate by Gary Chapman.

I am habitually suspicious of popular books on marital relationships. Most of them are simplistic or downright idiotic. So I braced myself to be disappointed.

BK summarized the book’s argument thusly:

Loving someone and making them feel loved are two different things. To make someone feel loved, you must understand the sort of thing that feels like love to him/her. Generally speaking, there are five ways to demonstrate that:

Words of Affirmation– Using words to build up the other person. “Thanks for taking out the garbage.” Not – “It’s about time you took out the garbage. The flies were going to carry it out for you.”

Of these five, Chapman posits, everyone has a primary love language that speaks more deeply to him/her than all the others. Discovering each other’s language and speaking it regularly is the best way for two people to keep love alive.

My immediate response to this: “This is silly.” But then BK asked, “Which one do you respond to? Which one feels most like love?”

And that sort of shocked me. Because there was an answer – a definite answer – and it came to me directly from the deepest part of my emotional brain.

“I respond to Words of Affirmation,” I said.

“And what about K?” he asked.

I knew the answer to that, too. I knew in some very clear and certain way that K’s answer would be “Acts of Service.”

I thanked BK for the insight. I admitted I’d never even thought about the possibility that feeling loved is different for different people. I actually felt embarrassed, because I’ve spent a fair amount of my thinking life on the subject of love and this was completely new to me.

I thought about the ways I express love to K, and they covered the range except for one: Acts of Service. And I thought about the ways K shows her love to me. Service is a big part of it, but she’s frugal in the Affirmation department.

So that was something else to think about – the fact that we are each parsimonious with the one thing we want for ourselves. And is that an ironic accident or a subconscious decision?

I should pause here to say that if all this sounds only too obvious to you, you will understand how I felt. Here I was, a year away from my 70th birthday, learning something I should have learned in high school.

I tested the Five Love Languages hypothesis the next morning by doing something for K that I wouldn’t normally have done. It was a small action. A modest gesture. And sure enough, she was taken by it. She even mentioned it later to her sister in front of me.

“Gee,” I thought. “This is powerful! I ‘ve got to do more of it more often.”

But… and this is a big “but.” If you think about the complexities of any relationship – parent/child, husband/wife, brother/sister, and friendships – you can readily see that keeping the relationship balanced and healthy requires more than simply making the other person feel loved. Other skills are involved. You have to know how to stand up for yourself. You have to know how to have a civil disagreement and how to compromise.

So, yes, I am going to practice this new skill because I want K to feel loved. But I’m also going to practice the other relationship skills because… well, because love is complicated.

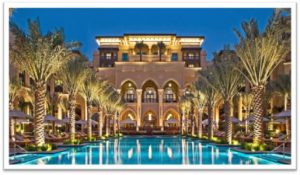

Last week Agora had its global publishers meeting in Dubai.

We chose Dubai because it was a compromise location for our publishers that travel from Europe, the Americas, and the Far East. And also because it is a destination that few of them had ever been to.

Dubai is worth seeing. It’s a glittering, ultra-modern city-state built mostly in the last 20 years. And it’s immensely impressive in many ways. Its hundreds of glass and steel skyscrapers are tall – very tall – and very attractive. (If you like glass and steel buildings.) It is incredibly clean. During the six days we were there, I spotted no more than a half-dozen cigarette butts on its pristine streets. It boasts all sorts of world records: the tallest building, the tallest hotel, the largest indoor shopping mall, the biggest aquarium, the longest automated rail network, and the largest indoor ski park, to name a few. And its best hotels – in terms of elegance, amenities, and service – are equal to or better than any that I have experienced.

I wasn’t able to do much writing during the week because the conference ran from 8:30 to 6:30 or 8:30 every day. It was not much fun for K, who had agreed to come along because I had agreed to spend the following week, this week, touring Jordan. The conference ended on Thursday night, so we had to see all the major tourist attractions on Friday and Saturday morning. That turned out to be enough time. Dubai’s attractions are the sort you’d find in Las Vegas minus the fun stuff – like gambling and shows.

And it was hot. Brutally hot. With temperatures ranging from 100 to 120 during the day and dropping to 90 at night. The air was so humid my glasses fogged up every time I stepped outdoors.

But I shouldn’t complain. I was there to work. Our global publishing groups have become a significant part of our business, representing more than a dozen countries and hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues. Most of them face the same challenges we face in the USA: a competitive Internet publishing environment that is essentially ruled by the whims of Google and Facebook and the other large social media platforms.

Each of the publishers made a presentation about their significant triumphs and failures. What works in one country doesn’t necessarily work in another – but it can. And when it does, it can mean the difference between profit and loss, and growth and stagnation.

I made the final presentation: “10 Things I’ve Learned About Our Business in the Last 40 Years.”

When I submitted the title, I had no idea what those 10 things would be. Not the first time I’ve done this. I pick an audacious title – one that is likely to attract attention. Then I challenge myself to write something that measures up to it. This is not, however, a methodology that I would recommend. It can easily – at least theoretically – result in disaster. But it does raise the bar. In this case, given the fact that I was speaking to a group of very smart and accomplished senior people in our business, the bar was very high indeed.

What could I talk about? Sales and marketing techniques? No. They constantly come and go. My thoughts about current business conditions? No. They, too, would soon be passé. I decided to focus on something that never changes: the most important element of business success.

I once heard a TED Talk on this subject. The speaker posited that there are 5 major factors: ideas, management, timing, capital, and people. If I remember correctly, his choice for “most important” was timing. And although I understood his reasoning, I had a different perspective.

For me, the most important factor is people – the people you hire to make your business work.

Timing matters. But timing is something you can’t control.

Ideas matter. But without fantastic people making those ideas real, they evaporate like smoke.

Management matters. But management works only if you have good managers.

Capital matters. But much less than most people think. There is no amount of capital that will make a good business from a bad idea. And there are countless examples of poorly capitalized businesses that succeeded due to the intelligence and hard work of their employees.

To my mind, that makes hiring, training, motivating, and compensating extraordinary people the most important job of every one of our publishers. (And, by the way, of every CEO of every business.)

And once I had that nailed down, it wasn’t hard for me to come up with 10 bullet points for my speech.

In a future blog post, I’ll give you all 10. For today, I just want to emphasize one of the main points I made:

When you look back at a successful entrepreneurial career, it often looks like dumb luck. And many successful entrepreneurs, when asked about their success, often claim, modestly, that it was indeed luck. But if you ask them to elaborate, you’ll find (as Jim Collins famously said) that most of their “luck” had to do with putting the right people in the right seats.