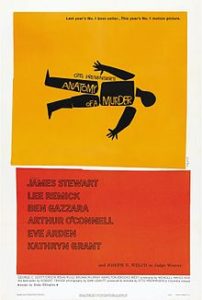

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Directed by Otto Preminger

Starring James Stewart, Lee Remick, and Ben Gazzara

Anatomy of a Murder was shot in black and white – mostly indoor scenes – and directed by Otto Preminger (whom I knew virtually nothing about before seeing this, but it turned me into a fan).

The plot is simple: A small-town Michigan lawyer (James Stewart) defends and succeeds in exonerating a US Army Lieutenant (Ben Gazzara) arrested for murdering an innkeeper that raped his wife (Lee Remick). The defense is temporary insanity.

As a courtroom drama, Anatomy of a Murder is not particularly profound, by, say, Inherit the Wind standards. But there are some clever legal and procedural jousts between Paul Biegler, the defense attorney (played by Stewart) and the two prosecuting attorneys (played by Brooks West and a young George C. Scott). And the many brief scenes involving the judge were so amazingly good that I said to K, “This guy has to have real-life courtroom experience.” Sure enough, he did! The judge was played by Joseph N. Welch, the lawyer famous for confronting Joseph McCarthy during the Army-McCarthy hearings. (He’s the one who said, “Have you no decency, sir?”)

Welch’s scene-stealing scenes, Jimmy Stewart’s acting, and the almost shockingly seductive beauty of Lee Remick are enough to merit the two hours you’d have to invest in this film.

Throughout the movie, K and I were disturbed by a dozen or so smallish things that made it difficult to decide what the facts of the case really were, and even which of the characters we could believe.

Was the Lee Remick character really raped, or did she claim to be to put her husband in jail and run off with her lover? Or was the story concocted by her and her husband, the murderer? And what about the Jimmy Stewart character? Was he a legal version of Mr. Smith (in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington)? And if so, why did he encourage his client to “remember” that he was temporarily insane? And if the couple were truly victims of a terrible rape, why, after Stewart won the case for them, did they leave town without paying him?

Thinking about it later, it occurred to me that the plot beneath the plot is one of moral ambiguity: A small town lawyer triumphs by guile, stealth, and trickery – and in doing so, frees a murderer.

In fact, all three of the main characters were culpable of unethical behavior.

* Lt. Manion is jealous and prone to violence and possibly abusive.

* Laura is manipulative and insincere. She admits to taking advantage of her beauty by being flirtatious.

* Biegler thinks of himself as principled, but subtly coaches Lt. Frederickson into inventing the defense of temporary insanity.

And that brings me back to Otto Preminger. A brief look at his filmography suggests that he had a preference for movies with challenging moral themes:

* The Moon Is Blue (1953), a comedy, was criticized for taking a flippant view towards sex.

* The Man With the Golden Arm (1955) focused on a heroin addict.

Critical Reviews

* “Simply the best trial movie ever made,” (Kim Newman in Empire Online)

* “Spellbinding all the way, infused by an ambiguity about human personality and motivation that is Preminger’s trademark.” (Jonathan Rosenbaum in Chicago Reader)

* “Coolly absorbing, nonchalantly cynical.” (Jessica Winter in Time Out)

Interesting Facts

* The opening credits are very cool.

* The movie is based on the book by Robert Traver, the pen name of Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker. The story is based on a murder case in which he was the defense attorney earlier in his career.

* This was one of the first mainstream Hollywood films to challenge industry censorship guidelines (the Hays Code) and address sex and rape in graphic terms. Dialog included the first on-screen use of such words as “intercourse” and “semen.”

* Duke Ellington (who appears in the film) wrote the Grammy-winning score.

MarkFord

MarkFord