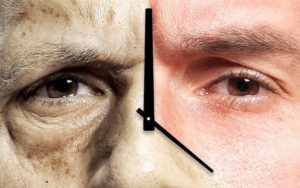

Feeling My Age… Finally!

I’ll be in Myrtle Beach for a week in October, a yearly get-together with some life-long friends, playing golf, watching football, talking shit, and reminiscing. We’ll rehash old stories about the halcyon days of high school. And there may be some private conversations about the harrowing days in Vietnam. There will be proud accounts of our progeny, ruminations about how the world is going to hell in a handbasket. And there will be lots of self-deprecating remarks about how our golf games, and all the other activities we engage in, are degenerating due to our age.

I was thinking about that aging issue. And it occurred to me that during each decade of my life, I’ve had a different perspective.

Seven Decades; Seven Relationships With Time

During my first decade of life, becoming older was an unquestioned good. Something looked forward to with unbridled anticipation. Becoming six would be better than being five. As being eight would be better than being seven. The value of becoming older in that first decade was such an obvious improvement in life that I measured my age in half-years.

Becoming older was equally desirable in my second decade. Each birthday made me in so many ways better off than I had been in previous years. My allowance went up. My responsibilities increased. And what modest liberties my parents gave me expanded. At 17, I enjoyed the height of social status in high school as a senior. The only thing I resented was that I had to wait until October of my freshman year in college to get a legal ID.

In my 20s, the eagerness I had always felt to become older faded. It was gradual. I don’t think I even noticed the change. But looking back at that time now, I can understand what happened. In my 20s, I was at the peak of my physical and mental fitness. I was strong, smart, and quick. I was also learning at the speed of light. I felt like there was nothing I couldn’t do. And that I would never die. I didn’t want to be older because I didn’t need to be older. Becoming 30 would give me nothing that I didn’t have already. I was a 20-something young man, at peak power and confidence, living the dream. The world was my oyster.

As I approached 30, however, I rued the fact that I’d soon be passing out of my 20s. Being 30 wasn’t terrible. But it wasn’t peak performance time either. I wasn’t quite as quick in my reflexes as I had been. I remember distinctly the moment when I failed to execute my go-to ball-stealing move in basketball. My mind said “Go.” And my legs said “No!” I began to look for other physical signals that I was “getting old.” And I made a commitment to resist them by incorporating strength and cardio conditioning into my everyday life. I did that. And it helped. The quickness I once had was gone for good. But I was able to maintain my strength and flexibility and stamina.

Turning 40 was another milestone in my relationship with aging. In terms of physical strength, I still had a sufficiency. But my speed and stamina were now waning, along with the quickness. My brain was still firing on all pistons. If anything, I was thinking better than ever. But I could no longer hope to compete physically with younger people. To compensate for the deflating effect this had on my ego, whenever a younger person would outperform me in a physical activity, I would remind him or her that I was “an old man.” And if I happened to win, I could not refrain from reminding my opponent that they had just had their ass kicked by a 40-year-old!

In the decade from 50 to 60, my body continued its slow but steady degradation in terms of quickness, speed, and stamina. But for the first time, I was also losing strength. This was, of course, predictable. (There are competitive weightlifters and even fighters in their 40s, but none in their 50s.) But the loss of strength was difficult to accept. Not because I needed the strength in my daily life, but because it foretold the loss of other capacities.

From 60 to 70, I could, for the first time, refer to myself un-ironically as an old man. I had lost any hope of keeping up with the strength, stamina, agility, or speed of younger people. In Jiu Jitsu, I could win matches against younger opponents, but only if I were technically more advanced than they were. In overall physical terms – i.e., horsepower and athleticism – the kids were miles ahead of me. This I knew I had to accept. And I adjusted to it. At the same time, I had to face another side of aging – the gradual disintegration of my skeleton and heart and lungs all my other vital organs. I have been lucky with that so far. But I was surrounded by friends that were dealing with all kinds of medical problems. That cast a shadow.

And now here I am, almost 72 and very much aware that in eight years I will turn 80. I will continue to dig my heels into the downward slope of my aging, but for the first time ever, I feel like I’m not a younger version of someone my age. I’ll continue to fight the noble fight as hard as I can, but I am also accepting that I will be encountering new physical and mental degradations. And while I’m doing that, I will be seeing something that so far has been out of my range of vision. I’m talking about the specter of death, standing somewhere behind that next milestone at 80.

In my 20s and 30s, I didn’t think of death at all. In my 40s and 50s, it felt like a lifetime away. In my 60s, it was a thought, but only an occasional one. But now I can see it just around the next bend.

The average life expectancy for healthy 70-year-old men in wealthy countries, the data people tell us, is somewhere in the range of 80 to 85. That means I could be in the ground in as little as a decade. And that thought is in the back of almost every decision I make.

MarkFord

MarkFord