Why I’m a Conservative, Part II

I’ve always admired the way some traditional cultures value the elderly. The older women are depended upon for advice on matters that were traditionally handled by women, including feeding, clothing, and caring for the family. The older men are depended on for advice on matters that were traditionally handled by men, including negotiating agreements.

In these societies, grandparents aren’t left alone in the houses that their children grew up in. Nor are they deposited in retirement homes. On the contrary, they move from actively participating to an equal or possibly more important role: overseeing decisions that the next generation wants to make, and sharing their thoughts and feelings about the wisdom or lack of wisdom of those decisions – often by recounting stories about similar decisions they have made.

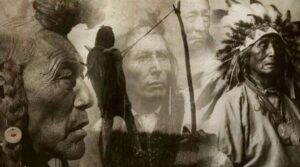

There are many such societies – but today, I’m thinking primarily of the Indians. (Oops! I mean Native Americans!)

Six Native Americans in a Tent

In my imaginary and very generalized picture of a traditional Native American village, I see five men – three young men in their twenties and two middle-aged men in their forties.

They are sitting in a small semi-circle, having an animated discussion. Apparently, a neighboring tribe has killed – accidently, they claim – a member of the tribe who inadvertently wandered into their territory.

The three young men are furious. They want quick, certain, and terrible retribution. Their plan is to raid the other tribe that very night, burn down their tents, kill all the men, rape the woman, and kidnap the children.

The two middle-aged men are not so gung-ho. They say they understand and agree with the younger men’s basic sentiments. But they argue that now is not the time. The other tribe will be expecting a counterattack. It would be better, they say, to catch them off guard.

Unable to agree on a course of action, they decide to ask the chief for his advice.

The chief is in his sixties or seventies. Maybe older. When they arrive at his tent, he is sitting outside, one of his grandchildren on his knee.

“We are here for your counsel,” the men say.

“Yes,” the chief says, lifting the child from his knee and handing it to his wife. “I was expecting you. Come inside.”

They enter the tent and take their places around a small fire.

“Before we begin,” the chief says, “let us smoke this pipe to bring us together as one spirit.”

When the smoking ritual is completed, the chief listens to each of the five men in turn.

“I see,” he says.

“So, what do we do?” they ask.

“First,” he says, “I have some questions.”

He asks his questions and listens to their answers. Then he picks up the pipe.

“Let us smoke again,” he says. “I have a story I want to tell you. I remember a situation very much like this one…”

How I See This Working in the Military

In Part I of this essay, I postulated that there are three levels of learning: ignorance, knowledge, and wisdom:

* Ignorance gives one the ability to believe almost anything if it’s repeated sufficiently.

* Knowledge gives one the ability to teach and lead the ignorant.

* And wisdom allows one to teach and lead the knowledgeable.

Here’s how that applies to the military:

The Ignorant are the recruits. The young men that have never been to war, and can only imagine (like me) what it is really like. In bootcamp, they learned about the mechanics of war, but they are completely ignorant of the reality of its horrors. And it is that ignorance that allows them to be stirred into doing the most incredibly courageous and stupid things by people they trust.

The Knowledge Keepers are the men that run the training programs designed to “ready” the recruits for war. Most of them have never been in battle themselves, but they have a good understanding of the tools, skills, and strategies of war, and many years of experience in teaching them. Their advanced knowledge of using weapons, driving tanks, flying planes, and so on, allows them to pass along what they know to the ignorant recruits. But their lack of experience in battle allows them to do something even more valuable: motivate the recruits to believe in the virtue of the war and go into it eagerly with fire in their bellies.

The Decision Makers are the troop and platoon leaders. The men who lead the recruits into battle. The men who have not just the knowledge but the years of experience and, thus, the instincts to confidently make on-the-spot decisions that will determine the outcome of every conflict for every young person under their command.

And then, of course, there are The Men Who Should Be Wise. The president and other elected officials that have the authority and responsibility to make the most important decisions. (Should we go to war? And if so, what is our commitment?)

In almost any group – whether it be a nuclear family, a military unit, a sports team, or a business – there is a natural and very healthy instinct to organize authority and responsibility in terms of the three levels of learning: ignorance, knowledge, and wisdom. When those given the authority and responsibility to make critically important decisions are respected as well as being wise, the likelihood of success is the highest. When they are not, difficult situations tend to go from bad to worse pretty quickly.

In Part III of this essay, I will tell you how the three levels of learning play out in business and personal affairs.

And then, I’ll try to show you how these universal patterns operate, or should operate, in our thinking about global relationships.

MarkFord

MarkFord