Search results

49 results found.

MarkFord.net

MarkFord.net

The open-for-inspection half-way home for my writing…

49 results found.

The Beginning of the Best Thing That Ever Happened

By Alexander Green

Journalists labor around the clock to deliver a distorted picture of the United States.

Their relentless drumbeat of negativity has convinced millions that we are a shameful and fatally flawed nation.

In a recent poll, Gallup found that only 42% of Americans are “extremely proud” to live in this country, a record low.

There is a sense among many that we are no longer an exceptional nation, that the country is in decline and the American Dream is over.

Today I’m going to offer an antidote to this poisonous perspective by sharing what radio broadcaster Paul Harvey used to call “the rest of the story.”

Consider the basic facts:

* Americans have never been richer. The Federal Reserve reported that US households added $13.5 trillion in wealth last year, the biggest increase in three decades.

* The stock market and home prices have hit new records. And Americans of all stripes have paid off credit card debt, saved more and refinanced into cheaper mortgages.

* Our homes are more expansive. (The average American living under the poverty line lives in a bigger home than the average European.) According to the Census Bureau, the median square footage of a new single-family home sold in 2020 was 2,333 square feet. That’s 53% larger than the median home built in 1973.

* Our standard of living has never been higher. Look at all the laborsaving devices, the huge variety of goods and services available, and the luxuries – from Ultra HD TVs to Starbucks’ lattes to high-thread-count sheets – that permeate your existence.

* Educational attainment has never been greater. Eighty-nine percent of Americans have a high school diploma. Sixty-one percent have some college. Forty-five percent have an associate or bachelor’s degree. (For comparison purposes, in 1952 only 6.4% of Americans had completed college.)

* The essentials of life – food, clothing and shelter – (in inflation-adjusted terms) have never been more affordable.

* Computers, laptops, tablets and smartphones – which are revolutionizing our lives – have never been cheaper or more powerful.

* We enjoy more leisure than ever before. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the average American workweek is 34.9 hours.

* Statistics show that divorce rates, domestic abuse, teenage pregnancies and abortions are all down.

* All forms of pollution – including greenhouse gases – are in decline.

* We are the world leader in technological innovation. The telephone, the television, the airplane and the internet were all invented here. So were blood transfusions, heart transplants and countless vaccines.

* If we are no different from other Western democracies, why were transformative companies like Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Twitter, Netflix, Snapchat, Instagram, PayPal, Tesla, Uber and Airbnb – to name just a few – all founded here?

* Consider, too, what American firms – like Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson – are doing to lead the fight against the global pandemic.

* Since 1950, approximately half of all Nobel Prizes awarded in the science fields have gone to Americans.

* Our space probes and orbiting telescopes explore and explain the cosmos. We put astronauts on the moon over half a century ago. And recent launches by SpaceX and Blue Origin demonstrate the technological prowess of our private sector.

* Americans are just 4.3% of the world’s population, yet we create nearly 30% of its annual wealth.

* Our economy is No. 1 by a huge margin. It is larger than Nos. 2 and 3 – China and Japan – combined.

* The US dollar is the world’s reserve currency.

* The American military – the primary defender of the free world – has never been stronger.

* American agriculture is the envy of the world. Our farmers now grow five times as much corn as they did in the 1930s – on 20% less land. The yield per acre has grown sixfold in the past 70 years.

* For decades, experts warned us that we had to end “our addiction to foreign oil.” Yet thanks to new technologies we are not just one of the world’s largest energy producers but a net exporter.

* The US also leads the world in science, engineering, medicine, entertainment and the arts.

* No nation attracts more immigrants, more students or more foreign investment capital.

* And Americans are the most charitable people on Earth, both in the aggregate and per capita. The Giving USA Foundation reported that US charitable donations hit a record $471.4 billion in 2020.

Despite our many blessings, polls show that Americans are less optimistic about the future today than in 1942, when we were in the fight of our lives against Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito.

Maybe we need a humorist to wake us up. As Dave Barry notes…

My mom, like my dad, and millions of other members of the Greatest Generation, had to contend with real adversity: the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, hunger, poverty, disease, World War II, extremely low-fi 78 rpm records and telephones that – incredible as it sounds today – could not even shoot video.

Your ancestors a few generations removed would view your life today as the realization of some utopia, a golden age.

We should celebrate our exceptional past as well.

Fireworks [fill the skies on July 4] because our nation’s founding was revolutionary – not in the sense of replacing one set of rulers with another but in placing political authority in the hands of the people.

Our Declaration of Independence is a timeless statement of inherent rights, the true purposes of government and the limits of political authority.

Our core beliefs are enshrined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights, the longest-serving foundation of liberty in history.

Our nation’s growth and prosperity have been extraordinary. How did our small republican experiment transform and dominate global culture and society?

Geography played a big role. Buffered by two oceans and a rugged frontier, we had plenty of cheap land and vast natural resources. (But then so did countries like Russia and Brazil.)

Entrepreneurs were given free license to innovate and create. Profit was never something to apologize for. Rather it was viewed as proof that businesses offered customers something more valuable than the money they traded.

We have opened our arms to tens of millions of immigrants who dreamed of a better life and helped to build this country.

We still take in more immigrants annually than any other country in the world. In the process, we have developed an astounding capacity for tolerance.

Racial tensions flared last year with the unconscionable killing of George Floyd.

But the mainstream media’s metanarrative – that we are a racist, sexist and homophobic nation – is unfounded.

Polls show that the vast majority of Americans today favor gay rights, interracial marriage and economic equality.

No other majority-white country in the world has elected a one-term – much less a two-term – Black president.

The average woman in the US makes less than the average man, true. But that is not de facto evidence of discrimination.

Studies reveal that after accounting for vocation, specialization, education, experience and hours worked, the difference between what men and women earn is negligible.

It is against federal law to pay a woman less than a man – or a Black person less than a white person – for the same work. (And we have no shortage of tort attorneys.)

As Gerard Baker of The Wall Street Journal writes…

Polling has consistently shown that, if they could, by overwhelming margins people from all over the world would choose to come here. Blacks from Africa, Latinos from Central and South America and Asians from Kamchatka to Kerala are yearning to live in the country we are told is defined by white privilege, xenophobia and ruthless oppression of minorities… What kind of enduring appeal must a country have, what kind of values must it convey to the world that it can so easily supersede the strenuous efforts of its own [media] to defame it?

I’m not suggesting that other nations don’t have proud histories, unique traditions or beautiful cultures.

I’m delighted when I get a chance to visit South Africa, Japan or Argentina, not to mention Paris or Rome. There’s a lot to love about day-to-day life in other countries.

However, people around the world don’t talk about the French Dream or the Chinese Dream. Only one nation is universally recognized as The Land of Opportunity.

That’s because America cultivates, celebrates and rewards the habits that make men and women successful.

Anyone with ambition and grit can move up the economic ladder. Everyone has a chance to improve his or her lot, regardless of circumstances.

As JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon noted in a Wall Street Journal op-ed piece…

America’s future has never been brighter. The US has the best universities, hospitals and businesses on the planet, and our people are the most entrepreneurial and innovative in the world, from the factory floor to the executive suite. We have by far the widest, deepest and most transparent capital markets, and a citizenry with an unparalleled work ethic and “can do” attitude.

American ingenuity, technology and capital markets have created dramatic improvements in communications, transportation, manufacturing, computing, retailing, food production, construction, healthcare, finance, pharmaceuticals, robotics, sensors, artificial intelligence, genetics, 3D printing and dozens of other industries.

These have benefited citizens not just here but all over the world.

Yes, the pandemic delivered a once-in-a-century setback. But it wasn’t a knockout punch.

Our amazingly resilient economy is already leading the global recovery.

The notion that America is an exceptional nation is not, as some would argue, just a crude strain of patriotism.

Our country embodies timeless ideals, an optimistic attitude and an enthusiastic endorsement of the pursuit of happiness.

Americans today are living longer, richer, freer lives than any people at any time in history.

Yes, we made mistakes along the way and face no shortage of problems and challenges today.

But this [year] Americans should celebrate the 245th anniversary of the beginning of the best thing that ever happened.

The Hidden Choreography of a Compelling (and Very Profitable) Marketing Tool

“Advertising is fundamentally persuasion and persuasion is not a science, but an art.” – William Bernbach

As a consultant to one of the world’s largest digital publishing networks, I’ve had the opportunity to see the interview-tisement develop gradually over the years, from the crude and amateurish efforts that were common 10 and 15 years ago to the kind that turn ordinary books into NYT bestsellers… make instant celebrities out of college professors, pastry chefs, and fitness teachers… and result in tens of millions of dollars in sales for the expert lucky enough to be endorsed by Oprah Winfrey.

As with the direct-marketing copy that you’re familiar with – whether you’re writing it yourself or working with a copywriter – the script for the interview must achieve credibility on several levels. Not only for the guru and the product you are selling, but (very important) for the host himself. And the way you establish his credibility is to have him play the role of skeptic – in a moderate, reasonable, likable way. If he is not likable (both to the guru and to the audience), the interview is not pleasant to watch. It becomes emotionally complicated, and the message is lost. (This is the big secret that Howard Stern learned in his journey from shock jock to perhaps the best interviewer in America.)

Introducing the Guru

You begin with the host on camera, speaking directly to the audience. He is holding research reports in his hand, which he will refer to a bit in introducing the guru, and perhaps later in the interview.

The introduction should initially be about the guru’s credibility, not track record. When it is all about track record, it becomes obvious to the audience that they are about to watch a con job. So the host begins with whatever you have about the guru that is universally recognized as credible… a good educational pedigree, a prior position with a prestigious post, a mention of publications, etc. After announcing the guru’s formal credentials, the host mentions the new idea/ system/ whatever that the guru has been invited to talk about. And he describes it in a way that is relevant, arresting, credible (again), and offers an indirect promise of some kind.

At this point, the host might take a look at his research reports and read a few things about performance and perhaps a few testimonials.

Until now, the host is NOT at all skeptical. There is no reason for him to be. He could evince the slightest gesture or the smallest comment of skepticism when he mentions a hard-to-believe performance claim, but that is all. His job during the introduction is not to confront the guru, but to give the audience a reason to think, “Wow, this is going to be interesting!”

The First Impression

The introduction ends with the host welcoming the guru to the show. He does this by turning away from the camera to where the guru is seated.

(Note: Until now, the camera has been on the host only. This is important. The guru should not be seen until the entire introduction is completed.)

In response to being welcomed to the show, the guru smiles and says, “Thank you.” And maybe, “Happy to be here.” He does NOT start acting like a cheesy infomercial guest, barking, “I’m really excited to be here… I have so much I want to say” crap. The goal here is for the audience to see him as modest, likable, and approachable.

And, by the way, this is the protocol of every good and serious TV interview program that exists. Check for yourself if you do not believe me. Even if the guru is Tony Robbins, you will see that when he is interviewed he does this simple smile-and thank-you bit.

The First 2 Questions

This is where the host begins the transition to intelligent, skeptical interviewer, acting as the representative of the audience, including the most skeptical of them.

That said, his first question should be only moderately skeptical. So it could, for example, be about some hard-to-believe statistic from the guru’s track record. But posed in a way that does not really challenge.

And in response to the undeniably amazing statistic that the host has just mentioned, the guru says something self-effacing, like, “Yeah, I got lucky that time.”

The host gives the guru a glance, saying, “Okay, you’re being modest” – and asks another such question.

This time, the guru admits that there must be something he’s done that is more than just luck. But he still makes an effort at modesty, presenting as someone who’s not looking to be in the spotlight. He’s there simply to answer questions about his new idea/ system/ whatever.

The Real Interview

The guru has proven himself to be honest and likeable and confident of his abilities… so now the real interview begins, and the tougher questions are asked.

How the guru answers these more challenging questions is of upmost importance. He should not appear to be reading marketing copy on a prompter. He should not look/ act like he is trying to sell anything. Rather, he is earnestly trying to explain how his idea/ system/ whatever works. He’s undeniably excited about it, because it is genuinely good and smart. His answers are carefully posed. He lets the facts speak for themselves.

A very powerful element of this portion of the interview is the “factual correction.” In posing what he thinks are tough questions, the host makes a statement that is incorrect. In correcting the error, the guru is kind and paternal, demonstrating once again his natural modesty and trustworthiness, but also his superior knowledge of the subject at hand.

During the course of the interview, there should be two or three such corrections, each one adding to the credibility of the guru and his brilliant idea/ system/ whatever.

And now, there’s a subtle change in the host. He has lost his skepticism. His questions now come from his genuine interest in and excitement about the idea/ system/ whatever – and the conversation flows quickly and with exuberance.

The False Close and the Real Close

The penultimate portion of the interview begins with the host (and the audience he’s representing) becoming a true believer. (“How can we get in on this?” he asks.) This is equivalent to the false close in a DM promo. The benefits are repeated and the offer is presented – but only matter-of-factly – by the guru. There is no need to pitch the product hard. The believers are believers.

Now, the extra bonuses and benefits are introduced and we get the “call to action.” Reading from a piece of paper that was given to him, the host might say, “According to your chief of marketing, audience members that want to take advantage of this today will be given…”

The guru responds by either acknowledging that or even being surprised by all the extras. As each one is mentioned, he adds some information about it.

And, finally, we go back to where we began, with the host speaking directly to the audience, emphasizing the great value they will get by responding immediately.

“People don’t buy art based on the personality of the artist. Or there wouldn’t be much art bought and sold.” – David L. Wolper

Buying Investment-Grade Art: An Inside View

There is so much bullshit in the art world. So many flakes and fakes and posers. The art business has always had a fair amount of graft and fraud, but in the past several decades this shady side of the industry has ballooned to the point where it may be larger than the legitimate market.

I’ve collected art for 40 years, and I had an art business for 20 years. I have no idea whether my thoughts on art are conventional or radical. They are based on my personal experience.

What I Know About Art as an Investment

Art has no intrinsic economic value. Unlike coal or oil or timber, it can’t be used to fuel trains, planes, and automobiles. The value of any individual work of art depends on the demand for it in the art market. And the strength of that demand is subjective.

If you stop to think about the supply of art, the millions – no, billions – of art objects that exist in the world today, you will have your first and most important lesson about art as an investment. And that is this: Most art, probably 98% of it, is barely worth the material it’s made from.

You are in Italy on vacation and buy an oil painting of a Tuscan landscape from a small gallery in Siena. You pay $1,200. But the moment you walk out the door, its value has probably dropped by 50% to 70% – and the only person that’s going to pay you the 50% is the dealer that sold it to you. And only if he thinks you’ll be coming back to buy more from him.

As the years go by, your Tuscan landscape changes hands, going from one person to another, and finally ends up in a garage sale or flea market. Its price at that time (adjusted for inflation) will almost certainly be less than $120, which means your investment would have lost 90% of its value.

This is not to say that if, instead of just letting it go, you offered it for sale now and then, you might one day find a buyer that values it as highly as you once did. It’s not likely, but it’s possible that you’d then get back your $1,200. Maybe even a bit more to cover inflation.

But as a rule, in purely economic terms, 98% of the world’s art objects aren’t worth the price you will pay for them – whatever that is.

Then there’s the other 2%…

For that very small part of the market that deals in a certain kind of art, the economics are very different.

Defining Our Terms

What is this little part of the art market where values rise over time and sometimes fortunes are made? What sort of art is that? How do you even define it?

You may have heard the following terms: fine art, collectible art, investment-grade art, and museum-quality art.

Of those four, let’s throw out “fine art,” because it’s meaningless. Of the other three, I don’t have a preference. But for the sake of simplicity (and because the topic here is investing), let’s use “investment-grade art.”

What makes one still life worth $100 while another, virtually identical to the average viewer, is worth $1 million?

Contrary to what many believe, it’s not a question of beauty. Or of brilliance. Or even technical virtuosity. It has little to nothing to do with all the descriptive adjectives you are likely to hear from a docent or auctioneer or read in a gallery brochure. In fact, it has little to nothing to do with aesthetics.

No, a piece of art becomes valuable because of its history. An artist’s work takes its first step towards historical importance when one or several influential critics come to the conclusion that it is important.

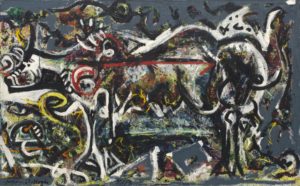

Jackson Pollock’s experience is a good example. For years, he worked in relative obscurity, producing the sort of abstractions that were popular at the time. Then the up-and-coming critic Clement Greenberg decided that one of the experimental pieces that Pollack had been doing was a work of genius… and he immediately started to be sold by Peggy Guggenheim’s prestigious Art of This Century gallery in New York City.

To give you an idea of how inexpensive Pollack’s paintings were back then, MoMA bought this piece – “The She Wolf” – for $650 in 1943:

Since the 1950s, Pollack has been included in every significant history book about modern art and has been taught in every art appreciation class. And in 2015, this “drip painting” (Number 17A, done in 1948) sold for $200 million:

Once an artist’s work is in the collection catalog of a dozen major museums, and has been selling at auctions for millions of dollars, and has made its way into the pages of respected books on art, there is virtually no chance its value will depreciate. That’s because everyone one involved with it – the collectors, the museums, dealers, and the uber-wealthy people that have bought it – have a vested interest in seeing the price rise.

Although investment-grade art can offer smart investors returns equal to or greater than stocks, and although the rules for investing in art are similar in some ways to the rules for investing in stocks, there are also differences. For example:

* The size of the market for investment-grade art is much, much smaller than the market for stocks (i.e., there are far fewer players).

* The number of factors that influence the price of investment-grade art are far fewer than the number of factors that influence stock valuations.

* Because of the above two facts, those that participate in the investment-grade art market, as a whole and even individually, have much greater control of market prices than do 99% of stock investors.

Put differently, the investible art market is a private club comprised of dealers, brokers, critics, auction houses, museums, collectors, and investors. And unlike most other markets, all of these diverse players benefit from the same thing: the gradual and steady appreciation of the art product ad infinitum over time.

Each does his part. The dealers manage the artists and their production. The brokers buy and sell it. The critics promote it. The scholars memorialize it. The museums validate it. The collectors hoard it. And the investors profit from it.

Let me put this in more pragmatic terms…

From a long-term perspective, the single most important factor in the value of a work of art is the artist’s status in the art history books. Next to that is the number of world-class museums that own and display it. Another extremely important factor is the total market “capitalization” of the artist’s work – i.e., how many millions of dollars large corporations and wealthy individuals have invested in it.

The good news for first-time art investors is that all of this information is publicly available. In fact, most of it can be obtained quickly through Google searches and auction records.

As I said, I’ve been buying and selling art for about 40 years – which is about as much time as I’ve been an active investor in the financial markets. My experience has been that, although there are some similarities (like the advantage of buying blue-chip when you can afford it and holding it long-term), investing in art feels more like investing in historical artifacts than in stocks or bonds. In other words, buying a statue by Henry Moore is more like buying a Tiffany lamp than a share of Microsoft or Walmart.

If you think about investment art as historical artifacts rather than as objects of beauty, and follow the common-sense rules one would follow when buying historical artifacts, your buying decisions will likely be sound.

“By prevailing over all obstacles and distractions, one may unfailingly arrive at his chosen goal or destination.” – Christopher Columbus

Against All Odds: Denver to LA in a Vintage RV, Part III

I woke up feeling conflicted about the luxurious meal we had at Lakeside, a top-rated restaurant in Wynn, a top-rated hotel.

The ambiance was what I had expected: plush and expensive in that over-the-top but still amazing Las Vegas/Dubai sort of way. (Did I mention that the Wynn cost $2.7 billion to build?) And the food was very good.

But it wasn’t any better than the meal we had at that diner in Green River at one-fifth the cost. It’s yet another reminder of something I’ve known for many years but keep forgetting: Paying more for luxury is seldom worth it. Spender beware.

Instead of beating myself up about it, I employed a simple but powerful trick I somehow figured out just last year in my 69th year on the planet: I forgave myself.

I had several hours before my 10:30 meeting. I looked for my laptop. It wasn’t on the desk. It wasn’t in my luggage. It was nowhere to be found. Yikes! I can’t live without it – not even for a single day. I called Lost & Found. It was closed until 9:30. I called the front desk and said that it was an emergency. They switched me to someone that said, yes, they had it.

I had left it at the bar I was sitting at after dinner. How could I have done that? Was this yet another symptom of early onset dementia? Or was it the wine and tequilas and fatigue? I don’t know. I forgave myself for the second time.

I got busy. At 10:30, we had the meeting. We were talking to our publishers, one by one, asking them how their businesses were doing. We actually know how they are doing, but we wanted to know if they are preparing for what could be a challenging year. I had asked for what I always ask for in such situations: three one-year business plans. One that is realistic, one that is optimistic, and one that is pessimistic. I’ve been doing this for 40 years. More often than not, the outcome is halfway between realistic and pessimistic. Rarely does the optimistic scenario turn out to be the reality, but it does happen. This year, it is happening with four of our 11 operating divisions. Still, I showed concern. I wanted to convey urgency. The Second Law of Thermodynamics mandates it. Even if it ain’t broken, I reminded our leaders, you should always be fixing it.

We left at noon, as planned. It was a glorious day – sunny and 70 degrees. Betty the Beast (an appellation I had given the Dodge) moved out on the highway proud and strong. Michael’s tape of 70s music was pumping. It looked like we would be in LA at 4:30 or 5:00. If all went well.

Forty minutes into this last stage of our adventure, Liam announced that the heat gauge was over 200.

“What’s the optimum?” I asked.

“About 200, plus or minus 10 degrees,” Liam said.

“So why are you concerned?”

“The margin is narrow. At 220, you could be in trouble. At 230, you definitely are.”

We pulled off to the side of the road, far away from the left lane where cars and trucks were whizzing by at 85 mph, to let the engine cool down.

I scolded myself for our optimism. We should have considered a worst-case situation before we left. But I’m a Ready-Fire-Aim sort of person. Apparently, Liam and Michael are too. I decided not to fuss about it. I forgave myself. I forgave us all.

Liam and Michael got to work consulting the manual and making phone calls. I found a shaded place nearby to sit and work. What would be the worst-case scenario? Betty the Beast would be too ill to carry on. If so, we’d tow her to a repair shop and then Uber to LA and retrieve her the next day.

After an hour, the engine had cooled down to 185. It was now safe to check the radiator. Liam did and found that the coolant had all but evaporated. That was actually good news. It meant that the overheating was due to a paucity of coolant. Liam filled it up. We climbed in. He started the engine. Betty roared to life.

“If things go well,” I told myself, “we’ll get to LA at 6:30 or 7:00. 6:30 is optimistic. 7:00 is realistic. 7:30 is pessimistic.” But that wasn’t true. Pessimistic would be another breakdown and missing our 8:00 dinner with our extended California family. We sent them a group text, letting them know the new ETA and promising to keep them updated every hour.

Driving through the desert, Betty struggled a bit on the inclines, the temperature gauge rising to 200 and even 210. But on the downhill, she cooled to a comfortable 190. Michael checked our altitude. We were at 4000 feet.

“I guess that’s good news,” I said. (LA is more or less at sea level.) “It’s mostly downhill from here!”

We arrived at Liam’s house at 7:45. Joanna, his wife, to our surprise, was delighted by the look of Betty the Beast. And the twins, Penelope and Fiona, were thrilled too. They called it the House Truck.

We arrived at the restaurant at 8:15. Number Two Son Patrick and his wife Jenny, Brother Chris and his son Vinnie, and Nephew Colin, the movie star, were there to greet us. We had a wonderful meal… all of us together and happy and with so much to talk about.

Mission complete!

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“If you don’t have a real stake in the new, then just surviving on the old… I don’t think is a long-term game.” – Satya Nadella

Is Automation Scarier Than COVID-19?

Does automation put people out of work?

Economists, politicians, and union leaders have been asking this question for as long as I can remember. And it’s a legitimate concern.

Consider driverless vehicles.

In the last 16 years, since the first DARPA Grand Challenge was held in the Mojave Desert, the race to develop a fully autonomous vehicle has been on. (See “Did You Know?” below.)

More than two dozen companies are working on it. The current leader is Alphabet Inc.’s Waymo, whose fleet of 600 vehicles have logged in more than 20 million miles. (Waymo stands for “a new way forward in mobility.”) And although we are not there yet, industry experts suggest that the first commercial autonomous vehicle will make its appearance in the next several years.

Considering the advantages (safer, cheaper to operate, etc.), it seems inevitable that driverless cars will replace conventional cars just as conventional cars replaced the horse and buggy.

How will that affect the workforce?

In Ride Sharing

I’m sure that Uber’s smartest executives are already doing the math on how much money they would save by replacing their 750,000 drivers with driverless vehicles. Add to those the drivers for Lyft, etc., and you’ve got about 1.5 million people out of work.

In Trucking

There are an estimated 1.2 million trucking companies in the US. When the trucking industry goes driverless, at least another 3.5 million Americans will be unemployed.

In the Bus Business

There are half a million school buses on the road, and another 600,000 commercial buses. Which means that 2 or 3 million bus drivers could lose their jobs.

And that’s not to mention the millions of UPS, FedEx, and other delivery service workers that will become obsolete when we have driverless vehicles and automated drop-off facilities.

What will all those people do?

Some Historical Perspective

The average American is not enthusiastic about the increased use of automation by just about every industry you can name. Many fear that it will lead to widespread unemployment and even greater economic inequality.

I have that fear myself. But the facts don’t support it.

When, for example, ATMs were introduced in the mid 1970s, it was thought that the jobs of tens of thousands of bank tellers were on the line.

That didn’t happen. Since then, in fact, the number of bank tellers in the US has doubled, from about 125,000 to 250,000.

The reason?

The hyper-efficiency of the ATMs gave banks more operating profits. And those profits were invested in opening new branches.

Thus, although the number of tellers at each bank did go down by a third, the number of branches increased by almost half.

It gets better.

Because the ATMs handle a majority of routine banking functions, tellers are freed up to to do more challenging – and higher-paying – work. (Such as customer service and loan processing.) And that means they make more money.

This is not to say that some jobs aren’t lost through automation.

From 1850 to 1970, the US agricultural sector shrank from 60% of the general workforce to 5%. Today, it’s 1%!

Manufacturing jobs, too, have been on the decline. Partly because some operations were moved overseas, but even more so through automation. In 1960, manufacturing workers represented 26% of the labor force. Today, that number is barely 9%.

But here’s the thing: Except for the Great Depression and the Great Recession, US employment opportunities, in general, did not shrink. On the contrary, they expanded.

One example: In 2012, after putting robots to work in its warehouses, Amazon was accused of being “determined to profit by creating a future where automation replaces good jobs.” But within a year, instead of having fewer employees, Amazon had added nearly 30,000.

Out With the Old…

When I was starting out in business in the late 1970s, every executive I knew had a secretary.

Being a secretary was a decent job for a smart person with a high school education and good typing skills. You could make $14,000 a year with benefits. But it was also mind-numbing. All you did was type, file, answer the phone, and book appointments.

Today, thanks in large part to computers and changes in the way businesses are run, secretarial jobs have pretty much disappeared. (My primary client has more than 1000 employees, and I don’t think there’s a single secretary among them.)

So what are all the people that once might have been secretaries doing? They are event planners, graphic artists, paralegals, personal assistants, and freelancers in dozens of fields – jobs that didn’t exist 50 years ago.

In much the same way, that’s what automation is all about.

Yes, automation replaces human labor. But countless studies, both in the US and in Europe, have found that innovations in technology, particularly in automation, have actually created more jobs.

What’s happening, I think, is this: By lowering the cost of the dullest and most tedious forms of human labor, automation generally increases profitability. A general increase in profitability stimulates economic growth. And when the economy grows, new jobs are created in every industry. Jobs that are more demanding, more interesting, and more financially rewarding than the ones that were lost.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“Collette said hope costs nothing. But it does. It costs the time you spend hoping.” – Michael Masterson

The Corona Economy: How Bad Is It… Really?

It’s time for another look at our Corona Economy. Time to assess the amazing amount of economic damage the shutdown has caused and make some guesses about how long, how bad, and how widespread the coming recession will be.

Recession? What? You think that things are under control? You feel confident that the economy will bounce back once we get this virus thing out of the way?

This is the way I see it…

The US economy is shrinking.

In my May 1 blog post, I noted that since the Corona Crisis began, our national production was down $10 trillion. That’s $10 trillion that was lost forever. No matter what happens in the future, that loss cannot be erased. In the three months since then, GDP has continued to shrink. In the second quarter alone, it fell by 10%. That’s higher than any 3-month period in the history of our country.

Unemployment is still crazy high.

The unemployment rate has gone down considerably since it peaked this spring, with jobless claims down from nearly 7 million in the third week of March to 1.2 million last week. Overall, the official unemployment rate has dropped from about 13% in April to 10.2% today.

Of course, the official unemployment rates are entirely bogus. They don’t count people who are unemployed and not looking for work. This number was about 6 million before the $600 giveaways. It’s probably 10 million now. Plus, the official rates don’t include part-time workers that want, but can’t find, full-time jobs. And on top of that are the problems with the way workers are classified. The most egregious: Those on furlough are counted as working, rather than as unemployed.

If you add back in those purposeful and possibly accidental errors, the actual unemployment rate is probably about 16%, which would make current levels higher than at any time since the Great Depression.

200,000+ businesses have been closed for good.

According to a study by the University of Illinois, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, and the University of Chicago, more than 100,000 small businesses had shut down permanently from March to the beginning of May. In June and July, another 100,000 may have been shuttered.

“We are going to see a level of bankruptcy activity that nobody in business has seen in their lifetime,” James Hammond, chief executive of New Generation Research told The Washington Post. “This will hit everyone, but it will be harder for small businesses since they don’t have a lot of spare cash.”

And Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, predicts that total failures for small businesses this year will pass 1 million.

It goes without saying that the closing of hundreds of thousands of small businesses will have a domino effect on hundreds of thousands more, the little shops and restaurants that survive on the patronage of these small businesses in small communities around the country.

Entire industries have been decimated.

Travel bans have gutted the transportation industry, drastically cutting not just airline revenues but train travel, bus travel, and car travel. Uber and other such businesses are down more than 75% since last year.

The near halt in travel has sent oil prices tumbling, putting thousands of businesses that support oil and gas distribution out of business and millions more Americans out of work.

In the retail sector, it’s not just small shops and restaurants that have been forced into bankruptcy, it’s beauty shops and fitness studios and day care centers. The list goes on and on.

But things don’t seem so bad… right?

I know. The unemployed have been getting federal paychecks. Businesses are getting billions in loans. And the stock market has been charging along.

That don’t change the facts.

When I last wrote about this (May 1), I noted that the numbers then were worse than they were at the nadir of the Great Recession of 2007-2009. And that even though the Great Recession officially ended in June of 2009, the growth of the GDP afterwards was anemic. Well… except for a modest improvement in the phony unemployment rate, all the key economic health indicators have only gotten worse.

Remember how difficult it was to make ends meet from 2009 to about 2016? It could be worse this time.

What about the bailout? Shouldn’t that help?

The coronavirus scared the hell out of millions of Americans, with studies predicting mortality rates of 6% and 3 million dead before the end of the year.

It was a national health emergency that could have united the country. Instead, it morphed into a ludicrous political drama, with the Democrats accusing the Republicans of being heartless and incompetent, and the Republicans accusing the Democrats of exaggerating the danger to tank the economy and bring Trump’s ratings down.

When it came time to pass an economic stimulus bill, partisan politics continued. The first round of bailouts cost US taxpayers $2.4 trillion that the Treasury had to borrow. And that was on top of $2.2 trillion approved to cover the budget deficit. The current package will add another $1 trillion to $3 trillion to that, bringing the total national debt to $25 trillion or more.

That – spending trillions of dollars we don’t have – has been the government’s solution to an economic disaster that is as bad as any we’ve had since the Great Depression.

Let’s stop here and remind ourselves that debt and spending have been the primary causes of every economic disaster the US economy – and, for that matter, every economy – has ever had.

If your kid were in debt because of a gambling habit and told you he was going to get himself square by borrowing money from a loan shark, would you think that was a good idea?

So that’s the real problem. We may never know how necessary it was to shut down the economy, but the solution to the economic damage it did has been a borrowing spree greater than ever in our history (and in the entire world).

And nobody in Washington thinks there is the slightest thing wrong! The old debate about responsible spending and balancing the budget has gone out the window. Those free checks from the government have bought the hearts and minds of the entire electorate. We may be doing something we’ll regret later, the most conservative say, but what the hell! Let’s print more trillions and wish for the best!

What to expect. What to do.

If you believe the stock market is the economy, I don’t know what to tell you. There are good reasons to believe stocks will continue to move up. The biggest reason is all these trillions of free dollars.

I have converted about 75% of my stocks into cash for reasons I explained on July 24. As I said then, my decision wasn’t based on any certainty that the market is going to crash, but on the possibility that it might.

If you understand that the stock market is not the measure of the wealth of the US but the measure of only the wealthiest 10%, you should be very concerned about all this debt and continued spending. You should be worried that sooner or later the bill will come due. And the only feasible way that the government can manage that debt is by allowing for an extended period of “moderate” inflation – low enough that the Treasury can pay the interest on its debt, but high enough that it can erode the value of that debt. And what that means is stagflation: years and years of increasing prices without any significant economic growth.

Unless you are already wealthy, this means that you will get a lot poorer over the next 5 or 10 or even 15 years.

There are things you can do to protect yourself and profit. I’ll tell you about it in my next essay on the Corona Economy.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

Ever since Trump took office, conversation with many friends and most of my family has been a challenge. They feel about him the way some of my conservative friends and colleagues feel about Hillary Clinton. When feelings are strong, reason declines and facts lose their context. I like a loud argument as much as any Irish American, but I don’t like an intellectual joust that leaves emotional bruises. Those bruises last longer when ideology insinuates itself into argument. Ideology leads to groupthink. Groupthink leads to war. And war is always destructive.

When news of the coronavirus broke, there was every reason to believe we were in a global crisis. Crisis often galvanizes otherwise opposing factions to band together against a common enemy. I hoped, naively, that this would be the case. Alas, it did not happen. The threat of COVID-19 became, almost immediately, an ideological topic.

The reports we were hearing from China and Europe through the World Health Organization (WHO) were positively frightening. But the numbers associated with those stories didn’t make any sense. So I began to write about it and do some research on my own. The more I studied what was being said, the less I believed it. And when the shelter-in-place solution was introduced as the “scientific” protocol for reducing the eventual death rate from COVID-19, I was challenging it in my blog posts and conversations.

That was not well received by my friends and family members who were getting their information from the mainstream press. They were convinced not only that sheltering-in-place was the right course of action, they believed that the USA had been hobbled by Trump by not putting it into effect sooner. It didn’t seem to matter to them that Trump’s earlier doubts about it were not his, but the recommendations of the WHO, the CDC, and the White House panel of experts headed by Dr. Fauci.

We do agree on one thing: The Trump administration bungled its response to the threat. But my friends/family think the mistake was in implementing mass quarantines too late. I think the mistake was in implementing them in the first place.

Living in Fear of the Fear of COVID-19

“Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” – Ben Franklin

I want to resume my wrestling, but K is worried that I will catch the virus from a training partner and infect the family.

My brother-in-law is worried about the throngs of (mostly young) people that have descended on Atlantic Avenue and its restaurants since they reopened a week ago. “It’s all bullshit,” he says. “Nobody is keeping social distance or wearing masks. Even some of the servers aren’t wearing masks.”

My fellow members of The Mules, the book club I belong to, want to have our next meeting virtually, as we’ve had the last two.

It’s difficult for me to speak about the virus with any of them because I know they are seriously frightened. But I believe their fear is unsubstantiated by the facts. And it angers me to think that they have been prompted into that level of fear by politicians and media that are using this crisis to further their political objectives.

So when I do speak about it, I find it difficult to restrain my anger. I state my opinions in definitive terms in hopes of shocking my friends/family out of their panic. It is a foolish approach. My sister reminded me of that yesterday, and she was right. So I’m writing this today, another essay on what I’ve learned about the coronavirus and why I believe the fear they are living with is based largely on misinformation.

I want to begin with some facts. But before I do, I implore you to read these facts with an open mind. Keep in mind that they all come from sources that you probably trust: the WHO, the CDC, Dr. Fauci and team, and several dozen studies done by respectable research institutions since the last essay I published on the virus itself.

*Fact One: Based on current death rates, COVID-19 ranks 13th on the list of the ailments that people, worldwide, die from each day. It is exceeded by cardiovascular disease, cancer, respiratory diseases, lower respiratory infections, dementia, digestive diseases, neonatal disorders, diarrheal diseases, diabetes, liver diseases, kidney diseases, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDs. It is also exceeded by road injuries and suicide (which is on its way up). The number of people that die from cardiovascular diseases is more than 20 times greater. (This would not have been true had you made the comparison when the death rate was at its peak, but it is true now.)

You may be thinking that you are not interested in comparing COVID-19 to cancer or heart disease, since they are not contagious. In terms of my topic – which is fear – I think that is an illogical position. But put that aside…

* Fact Two: Of contagious diseases, it ranks 7th, after lower respiratory diseases, neonatal disorders, diarrheal diseases, digestive diseases, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDs.

The fatality rate of COVID-19 is the primary reason that some epidemiologists were so concerned about the disease in the first place. Early reports had it at double digits, then at 6%, and then at 3.4%.

Those were the numbers that spurred the call for mass quarantining. But those numbers were based on case fatality rates.

As I explained in every essay I wrote on the subject, this is an useless and potentially misleading statistic. The case fatality rate does not measure a disease’s actual lethality rate. It measures only how many people died compared to how many people have been diagnosed as positive.

We can only know the actual fatality rate (some call it the infectious fatality rate) when we know how many people have died compared to how many people have been actually infected.

That was impossible to determine in March or even April because test kits were limited and no one was doing randomized tests of people that showed no symptoms.

Those tests have been conducted in the last four weeks. And what they are showing us is that the earlier case fatality rates overestimated the true fatality rates by a factor of 10 to 50.

For example:

* Fact Three: A new randomized study of 3000 people in New York State found that 13.9% of those tested for antibodies were positive. That means 2.7 million New Yorkers have already contracted COVID-19. When this was reported, there were 257,216 cases with 15,302 deaths. That equates to a case fatality rate of 6%.

But as I explained above, the case fatality rate is meaningless until you know the number of people infected, not just the number diagnosed. I suggested in my April 8 essay that it must be at least 10 times higher because symptoms for so many were flu-like and because of the lack of testing available then.

Adjusting for the latest findings, we can see that the actual lethality rate is a bit more than 10 times case the fatality rate, coming in at about 0.5%.

* Fact Four: This same study found that 21.2% of those tested in New York City were diagnosed as positive for COVID-19 antibodies. New York City’s population is 8.4 million. Extrapolating on that, we can assume that about 1.78 million denizens of the Big Apple were already infected with COVID-19 at the time. This means that even in the worst hot spot in the country, the actual fatality rate was 0.6%.

* Fact Five: These findings are similar to those from antibody studies done in Santa Clara, CA; LA county; and Kansas. Dutch, German, and French studies also show a much higher incidence of the virus than case studies would suggest – which means much lower real lethality rates.

My friends and family members that have a different view than I do tell me that the actual death count from COVID-19 is higher than reported. They tell me that there were surely people that died from it in the early days that were not diagnosed. I don’t doubt that. But if you understand the protocols that were put into place in by the CDC in early March, you can deduce that this must be a fraction of the distortion that occurred during the period of time when the death count was in the thousands.

* Fact Six: The CDC’s recommendations for reporting COVID-19 deaths included patients that died with “symptoms” of the disease, even if they didn’t die “of” the disease. In other words, if a patient that died of pancreatic cancer happened to test positive for COVID-19, the cause of death should be noted as COVID-19. (Note: When the state of Colorado did a study of this recently, differentiating those people that died with COVID-19 symptoms from those that died of COVID-19, the COVID death rate dropped by 25%!)

It’s hard to understand why the CDC would have made this recommendation, since it is patently unscientific. Most symptoms of COVID-19 are similar to flu and other respiratory diseases. Even in hot spots, less than half of those with COVID-19 symptoms test positive. Several emergency room and ICU doctors have commented publicly on this anomaly, complaining that they feel pressured to report deaths as due to COVID-19 when there is no certain reason to think it is so.

A fatality rate of 0.5% is considerably higher than the 0.1% or 0.2% fatality rate of influenza. But as I have explained, there is an important difference between COVID-19 and influenza. COVID-19 does most of its killing among populations of older people that have other life-threatening, “comorbidity” issues.

* Fact Seven: A study by the AMA found that 94% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in New York City had serious underlying conditions. 53% had hypertension, 42% were obese, and 32% had diabetes. The median age was 63.

* Fact Eight: In New York, the fatality rate for COVID-19 patients between 18 and 45 is 0.1%. For children, the fatality rate is statistically zero percent.

These numbers correspond to the analysis I did in March. Also, multiple studies have shown that children are not significant “vectors” of COVID-19. That means they don’t spread it very well.

The chances of contracting COVID-19 are much greater in confined spaces than they are in the open air.

* Fact Nine: A Chinese study of 3000 COVID-19 deaths found that all but one of the patients contracted the disease indoors. (The one exception contracted it through contact with someone that had just arrived from Wuhan province.) Yet many state governors, like New York’s Cuomo, were forcing elderly COVID-19 patients into nursing homes – which accounts for the severe contagion and death rates that we saw in those facilities across the globe. (This policy has just recently been reversed, weeks after the results of this study were reported.)

There have been several new studies suggesting that herd immunity for COVID-19 might be much lower than the 60% to 80% that was originally projected. I haven’t had time to locate these studies, so I can’t call this a fact. I know the projections are between 10% and 40%. 10% makes no sense. But 40% could explain why we’ve seen the recent drop in mortality.

There is no disputing the fact that you can reduce the speed at which the virus spreads by social distancing and washing hands. This is the strategy of flattening the curve. But flattening the curve is about slowing the spread of infection – not necessarily decreasing the eventual death count – which is what happened because of measures like social distancing and hand washing, not the lockdown.

* Fact Ten: Studies from Germany and Switzerland found that the flattening of the curve of the contagion happened weeks earlier than originally believed. In every case studied, the peak appears to have been before lockdowns were implemented. What that means is that the lockdowns did not work. They were not the reason the curve flattened. They had, if any, only a negligible impact on the curves in those countries.

* Fact Eleven: According to an analysis by Stanford University, there is no statistical correlation between lockdowns and COVID-19 deaths between those states that locked down early and those states that locked down late.

Those are some of the facts. And all of them come, as I said, from the WHO, the CDC, and reputable university and scientific studies.

So this brings me to the point of disagreement I have with friends and family members that believe the lockdown was and still is necessary, and that the movement towards opening the economy puts them and others in danger of dying.

Spend five minutes thinking about the above facts, and you have to agree that the proper response to the coronavirus threat would have been to isolate the most vulnerable (which we did not do) and not shut down the economy.

In fact, there is an argument to be made that sheltering-in-place has caused and will cause thousands and potentially hundreds of thousands of additional deaths. Deaths from depression, suicide, and domestic violence, as well as the deaths of many people with symptoms of heart attack, stroke, etc. that should have gone to the hospital but didn’t because of the fear of getting infected.

* Fact Twelve: Vaccinations for children have abruptly fallen at an alarming rate since the shutdown. In Michigan, fewer than half of infants 5 months or younger are up to date on their vaccinations, which may allow for outbreaks in diseases like measles.

But I won’t make that argument. It’s more important to make another point.

Unless we develop a miracle vaccine in the next few months, there are going to be lots more people dying of COVID-19. We don’t know how many. But based on the facts I’ve listed above, I hope it’s clear that there will be no lowering of the death rate by any continuance of the lockdown.

And speaking of a miracle vaccine, we have seen an historically unprecedented acceleration of efforts, private and public, to find a vaccine. And according to reports on both sides of the argument, we are making progress. At least a half-dozen vaccines have been approved for initial, phase one testing.

But here’s another fact to consider:

* Fact Thirteen: 90% of drugs that are approved for initial, phase one testing fail to make it to phase two.

The logic behind the opinion that many hold – that mass quarantines will minimize future deaths because the spread of the virus will be slowed – is faulty. The opposite is the case.

The only valid purpose for the lockdown that ever made any sense was to flatten the curve and thereby prevent hospitals from being so overwhelmed that they could not properly treat COVID-19 patients. But I’ve not found a single report that verified a death caused by, for example, lack of access to a ventilator.

What the lockdowns did, without question, is slow the race towards herd immunity. That means (again, barring the development and approval of an effective vaccine in the next few months) we will almost certainly have a second and even a third wave of the virus. And when those waves come, they will likely be different – maybe more lethal – strains. Which would mean, for certain, that the lockdown strategy will have resulted in many more deaths.

That is what makes me angry. And that is why I am upset when I hear my friends and family members say that those that favor opening the economy are putting money ahead of lives. It’s simply not true. The facts don’t support it. If we want to reduce the eventual death count, we must allow the virus to spread among the large percentage of the population that has little to no chance of dying from it. We have to reach heard immunity before a new, more lethal strain comes back and infects us. (This, by the way, is what happened with the Spanish Flu of 1918.)

I am angry and I want to blame someone. But I can’t blame my friends and family members who are scared because of the misinformation they’ve relied on.

I blame the mainstream media for not investigating the pandemic with any seriousness. And I blame some newspapers and news programs for pursuing reporting that was evidently meant to scare people.

These reporters and commentators failed very early to do even the simplest arithmetic, which would have made them understand how misleading the early case fatality rates were. Since then, they have ignored the studies that have unearthed the evidence listed above. Why they continue promoting their false narrative is anyone’s guess.

But because they will continue to promote their false narrative, the people that have taken it for truth will likely continue to believe it. They will continue to find ways to blame the Trump administration for the deaths that will follow, ignoring the fact that the mistake it made is clearly the mistake of shutting the economy down.

As I’ll explain in a moment, though, none of that makes any difference. We are already fast into the opening process and that isn’t going to stop.

But before I get into that, a few words on what I think we should have done.

In retrospect, the smarter federal policy would have been to:

In retrospect, the correct response from the CDC and the president’s task force would have been to recognize, immediately, that the arithmetic that gave us “official” lethality rates of 10% and 6.5% and 3.4% (and the early predictions of millions of US deaths) was obviously wrong.

In retrospect, state and local governments should have kept parks and beaches open so that people could get the exercise and the sun they needed. They should have advised anyone concerned about catching the virus or passing it on to their elders that the likelihood of that happening in the outdoors is tiny compared with the chances of catching it in any sort of “sheltered” place.

In retrospect, we should not have required nursing homes to take back their clients that had been diagnosed with COVID-19. That’s what caused the spike in deaths that we saw. We should have isolated those people and, thus, reduced the huge percentage of deaths that occurred in such facilities.

* Fact Fourteen: 41% of the Americans that have died from COVID-19 were in nursing homes. In Minnesota, the percentage was 81%. In New Hampshire, it was 72%. In Rhode Island, it was 75%. In a dozen other states, it was more than 60%.

The coronavirus is very contagious. And it is lethal to older people that have serious comorbidity issues. But it is not lethal to the rest of the population. To most of those that have been put on unemployment – mostly younger, healthier people – it isn’t a great threat at all. And to those that are vulnerable, shelter-in-place increased their chances of dying from it.

Those are, it seems to me, the facts.

The curve has flattened in most of America, but COVID-19 has not been conquered. Not at all. It will come back and it will continue to kill. In one of my early essays, I predicted that it would kill between 60,000 and 120,000 this year and as many as 600,000 if we don’t reach herd immunity.

The lockdown did not and will not diminish that number. Only herd immunity (either acquired naturally by spreading the infection or with the help of a vaccine) will do that.

In retrospect, it would have been better to if the WHO, the CDC, and the administration had reduced, rather than inflamed the panic that has spread like a virus across our country. It would have been better if they had admitted, early on, that the original arithmetic and modeling were bad and waited for the facts.

I would like to think that anyone that that is fearful now could get a realistic grip of reality by focusing on these facts, but that may not happen. When you have invested so much emotional energy into a fear about the future, it’s difficult to give it up.

I doubt, too, that when this is over, those that have accepted the viability of the lockdown will change their opinions. They will be suspicious of facts that don’t support the narrative they have been sold. And the media and public figures that sold that narrative aren’t likely to admit that they were wrong either.

They make minor adjustments to their stories to accommodate realities that cannot be refuted, but will hold on to the scientific evidence that is more difficult for lay people to understand. They will do this to protect themselves from the shame they must feel when they think about what they have created.

For my part, I’m going to do my best to bite my tongue whenever I hear fearful friends and family members fretting about the opening up of the economy. Biting my tongue is an easy price to pay to avoid saying something that pisses them off.

A tougher issue for me will be how I go about taking advantage of all these openings. For one thing, as I said at the top, I want to resume my wrestling. That would mean rolling around on the floor with young guys who, if they had COVID-19, would likely be asymptomatic. I understand why K has forbidden me from doing that. I believe the actual risk is infinitesimally small, but being wrong is not chance I’m willing to take.

I will have to put off my favorite form of exercise until K’s fear subsides. And I realize that’s not going to happen until the pandemic narrative she has been listening to gives up the ghost of its beliefs about the lockdown and shelter-in-place strategies.

That will happen well before we have an effective vaccine. I can see it happening already. K had her hair done yesterday. My brother-in-law hugged a friend. It is people like this, not the protesters that have been opposing the shutdown, that will bring the American economy back to life.

They will do it not because they believe the shutdown was wrong, but because they are sick and tired of being locked up.

There is only so long that a mentally healthy person can stay locked up in a prison of fear.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us [LINK] for more information. [BOLD/CENTERED]

Contagious vs Infectious

An infectious disease is a communicable disease that spreads by contaminating people (or animals) with pathogenic microbial agents, such as viruses, bacteria, or other microorganisms. In other words, a disease where bad germs get into the body in some way, spread, and make you sick by affecting the way your body normally works.

Contagious (or communicable) infections spread through contact. Examples: chickenpox, cold and flu (influenza), malaria, Lyme disease, measles, meningitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, Ebola, MRSA, polio, hepatitis A and B, HIV/AIDS, and coronavirus.

“Performance is better than promise. Exuberant assurances are cheap.” – Joseph Pulitzer

The Corona Economy, Part II

Will America Survive It?

Alec writes:

Today marks the 29th day in a row that I have worn pants with a drawstring.

I went into Rand’s room this morning and woke him up. I said, “Rand, you have to get up.”

He raised his head up from his pillow and said, “Why?” Then he went back to sleep.

My wife is running a business with 10 restaurants and goes to work every day. She is busier than ever… as other restaurants gradually close, they are filling a growing number of carryout orders for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Her text this morning read, “Has at Costco $1.49.”

How she had time to text me, or what the text meant, I didn’t know. But thinking it might be vital information, I texted back, “WHAT??”

Her reply was, “G gas.”

I thought, “Wow, gas, $1.49 a gallon. I can’t remember when gas was that cheap. I’d better rush to Costco to get gas before they run out.”

I jumped into my car and backed out of the driveway. Then I realized: I hadn’t gone anywhere for 29 days. My gas tank is still full! (Later, I did the math and I am driving an average of 0.7 miles a day. I may not need gas until the middle of June.)

But America will soon be “opening up again.” Not because Donald Trump wants it to. Nor will it happen because we’ve passed the peak of the contagion. (There will be a second wave.) State governors will have lots to say about it, but they won’t actually make the important decisions. America’s people – its entrepreneurs, professionals, corporate executives, and employees will.

“Opening up” is bit of hyperbole. Our economy was never truly shut down. It was regulated into a crippled gait. In six short weeks, the US has experienced a financial collapse it hasn’t experienced in a hundred years.

As I write this, for example, more than 22 million American workers have filed for unemployment. Millions more will surely be filing in May and June. Both Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and the Fed’s James Bullard have said they believe that unemployment will bypass 20% and could end up higher than it was during the Great Depression of 1929.

The unemployment rate hit a record of 25% in 1933 – 4 years after the Great Depression – and remained over 14% during the entire decade of the 1930s. The highest rate since then was 10.8% in 1982.

Another concern: The 2008 financial collapse was triggered by mortgage defaults. What is happening today is just as serious – rent defaults. According to Rent Payer Tracker, as of April 19, one-third of the 13.4 million renters surveyed hadn’t yet paid their April rent, ordinarily due on April 1. An increase in rent defaults isn’t likely to collapse the economy by itself, but it reflects a trend I’ve seen even among friends and colleagues that are financially secure: People are reluctant to pay bills they don’t have to pay.

The big picture is the gross domestic product (GDP), the total output of the US economy. With so many businesses, large and small, inactive or unprofitable, Goldman Sachs projects that GDP could decline by 24% by the end of June.

Think about that. Total GDP output in 2019 was about $21.4 trillion. If it drops 24%, that’s an annual loss of over $5 trillion of economic activity. And that’s on top of the macroeconomic factors we covered in Part I of this series:

* The US government is currently in debt to the tune of $24 trillion.

* It’s been running at a $1 trillion annual loss for years.

* The Treasury itself is broke. Its bills exceed its revenues by several trillion dollars.

* The government recently spent $2.5 trillion it didn’t have.

* On the other side of the ledger, federal tax revenues will be at least $2 trillion less than they were last year.

Add it all up and you have an already broke government increasing its deficit by as much as $10 trillion in a single year!

The government is working furiously to avoid a total collapse. Their strategy is to give away trillions of dollars in paper money. They have already given half a trillion via the Payroll Protection Program and have committed to another half-trillion more. And that’s not counting the 1.5 trillion that went to bail out Wall Street.

As you remember from Monday’s essay, the US government doesn’t really have any wealth to distribute. It’s broke and is getting broker every day by billions of dollars. If, as I suggested, our government were a business, only a fool would invest in it or lend it money. But that’s how it’s been surviving these past several years – by selling Treasury bonds to the likes of China, Saudi Arabia, and Europe.

That’s of no apparent concern to some of our legislators and public thinkers. They are criticizing the giveaway so far for being too conservative.

Regarding the 20% to 24% projection of GDP loss, a NYT columnist said, “This time, with government deliberately shutting down commerce, it could well fall faster.

Only a World War II-scale response can make up that difference.”

And where will government get the money?

His answer: “At a time when inflation is close to zero and the government can borrow for 30 years at less than 2%, this is precisely the moment to borrow to underwrite a recovery that also modernizes the economy.”

Never before in US history has so much money been doled out so quickly and with so little understanding of or regard for consequences. Rarely have so many politicians from both sides of the aisle favored such a level of spending.

As Bill Bonner recently pointed out, the Small Business Administration giveaway is forcing banks to review and approve loans at a surrealistic rate.

“Every half a second,” he writes, “they’ve had to check out the facts… verify the value of collateral… and assure themselves that everything was on the level – after all, they were giving out as much as $2 million per application!”

“Who gets the money?” Bill asks. We can’t be sure. But when money is being given away so fast and furiously, there’s a good chance that much of it will be unproductive. “Like subprime mortgages in 2007,” Bill says, “All you need [to qualify] is a pulse. Even hedge funds are eligible.”

The millions that have been fired or furloughed will be getting a few hundred dollars a week while the shutdown continues. Meanwhile, the hundreds of US senators and representatives and their thousands of aides will continue at full pay while they try to spend our way out of all this mounting debt.

“Don’t worry,” they assure us. “We are going to take care of this.” Assurances from people that have never run a business and have little to no understanding of how a real economy actually works.

So what is it they don’t understand? We’ll talk about that on Monday.

“Imagine preventing health crises, not just responding to them.” – Nathan Wolfe

My Last Essay on the Coronavirus (I Promise!)

5 Important Questions; 5 Conclusions

Once again, we were having a family argument about the coronavirus. The topic last night was: “Why Donald Trump Is Killing People With His Plan to Reopen the Economy.” But after a good five minutes of perfervid shouting, it turned into an argument about how dangerous the virus really is.

“And now COVID-19 is the biggest killer in America,” J said.

“That’s not possible,” I said.

“I read it in The Washington Post.”

Now J has been right about that damn lefty rag before, so I had to check my facts. I tracked down the article this morning. It was published on April 16. The author had given COVID-19 the “biggest killer” title based on a single week’s data.

J was right. The article made that claim. But I feel that I was right too. Because the “fact” that it was on the top of some chart last week doesn’t mean it is or is going to be the leading killer this year. As always, it will be heart disease and cancer. Coronavirus will do its share of killing. It will make the top 10, edging out suicide, kidney disease, and maybe even pneumonia (from common colds and influenza). But I doubt it will edge out accidents, lower respiratory, cerebrovascular, and Alzheimer’s diseases.

Today, I’m going to try to answer the question of how deadly this novel virus is as part of what I promise will be my final essay on the virus itself. (I will be following up on Monday’s essay on “The Corona Economy” with two or three more essays, and then I’ll probably join the fray and register my view of how the crisis will change the way we live. But that will be it!)

There are four reasons this will be my final essay on the virus itself:

* I normally write about subjects I know, like business and wealth building and so on. It’s exhausting to have to research and check facts to support my conclusions about the virus.

* When I began writing about the virus in mid-March, I was presenting ideas that were largely contrary to what I was seeing in the major media. It was fun to make claims and predictions that seemed outrageous and might offend. But in five short weeks, the consensus of expert opinion, along with the media, has moved uncomfortably close to what I was saying then. I have no interest is presenting ideas that the world is accepting as true. There’s no point in it.

* My family, my editor, and even some of my loyal readers have asked me to stop. As SC said recently, “Enough already!”

* If we get the right kind of testing done soon – and it appears we will – there will no longer be an argument about the most important questions.

So what I’m going to do today is present my argument against The Washington Post claim, and then reiterate (with some revisions) the five most important questions and answers about the coronavirus and COVID-19.

Question One: Comparatively Speaking, How Deadly Is the Coronavirus?

Let’s begin with some big numbers. How many Americans will COVID-19 kill in 2020? And how will that number compare to America’s biggest killers?

I’m going to address the second question first, because part of it is easy to answer.

In 2018, the most recent year the CDC had published records for, the top killers were as follows:

The first expert estimates for COVID-19, you may remember, were 2 million to 3 million. Dr. Fauci and team’s first guess was 100,000 to 240,00. Just before they announced that range, I had come up with a range of 85,000 to 205,000, which was published in my March 30 blog. Shortly after that, Fauci and team dropped their estimate to 60,000. But that wasn’t meant to be the death toll for the virus itself. Just how many would die by August first.

So how many will die?

As you’ll see from my answers to the next several questions, that’s impossible to know until we know how many Americans (and other populations) have already been infected. Based on what I’ve seen, I’m sticking to my original guess. But I’m going to narrow down the range. My current guess is more than 85,000 but less than 120,000.

Conclusion and Prediction: COVID-19 is not the most dangerous health crisis Americans face today. It won’t come close to heart disease and cancer, but it will be significant, killing more than 60,000 but less than twice that.

Question Two: How Deadly Is the Coronavirus by Age Group?

Throughout March, the media focused a great deal on the fact that COVID-19 seems to be especially deadly to older people and people that have “compromised immune systems” or “comorbidity issues.” This had most of my coevals frightened.

Then, about two weeks ago, another narrative hit the headlines: It’s killing younger people too! Even babies!

And that scared the shit out of everybody.

Let’s take a look at these two claims by comparing CDC figures on deaths by age group for COVID-19 against deaths from cold- or influenza-induced pneumonia.

From the beginning of February until the middle of March, 682,565 Americans died.

Of those 682,565 that died, 13,130 (roughly 2%) died from COVID-19 and 45,019 (roughly 6.5%) from cold- or influenza-induced pneumonia.

COVID-19 Percentages (based on 13,130 deaths)