“People don’t buy art based on the personality of the artist. Or there wouldn’t be much art bought and sold.” – David L. Wolper

Buying Investment-Grade Art: An Inside View

There is so much bullshit in the art world. So many flakes and fakes and posers. The art business has always had a fair amount of graft and fraud, but in the past several decades this shady side of the industry has ballooned to the point where it may be larger than the legitimate market.

I’ve collected art for 40 years, and I had an art business for 20 years. I have no idea whether my thoughts on art are conventional or radical. They are based on my personal experience.

What I Know About Art as an Investment

Art has no intrinsic economic value. Unlike coal or oil or timber, it can’t be used to fuel trains, planes, and automobiles. The value of any individual work of art depends on the demand for it in the art market. And the strength of that demand is subjective.

If you stop to think about the supply of art, the millions – no, billions – of art objects that exist in the world today, you will have your first and most important lesson about art as an investment. And that is this: Most art, probably 98% of it, is barely worth the material it’s made from.

You are in Italy on vacation and buy an oil painting of a Tuscan landscape from a small gallery in Siena. You pay $1,200. But the moment you walk out the door, its value has probably dropped by 50% to 70% – and the only person that’s going to pay you the 50% is the dealer that sold it to you. And only if he thinks you’ll be coming back to buy more from him.

As the years go by, your Tuscan landscape changes hands, going from one person to another, and finally ends up in a garage sale or flea market. Its price at that time (adjusted for inflation) will almost certainly be less than $120, which means your investment would have lost 90% of its value.

This is not to say that if, instead of just letting it go, you offered it for sale now and then, you might one day find a buyer that values it as highly as you once did. It’s not likely, but it’s possible that you’d then get back your $1,200. Maybe even a bit more to cover inflation.

But as a rule, in purely economic terms, 98% of the world’s art objects aren’t worth the price you will pay for them – whatever that is.

Then there’s the other 2%…

For that very small part of the market that deals in a certain kind of art, the economics are very different.

Defining Our Terms

What is this little part of the art market where values rise over time and sometimes fortunes are made? What sort of art is that? How do you even define it?

You may have heard the following terms: fine art, collectible art, investment-grade art, and museum-quality art.

Of those four, let’s throw out “fine art,” because it’s meaningless. Of the other three, I don’t have a preference. But for the sake of simplicity (and because the topic here is investing), let’s use “investment-grade art.”

What makes one still life worth $100 while another, virtually identical to the average viewer, is worth $1 million?

Contrary to what many believe, it’s not a question of beauty. Or of brilliance. Or even technical virtuosity. It has little to nothing to do with all the descriptive adjectives you are likely to hear from a docent or auctioneer or read in a gallery brochure. In fact, it has little to nothing to do with aesthetics.

No, a piece of art becomes valuable because of its history. An artist’s work takes its first step towards historical importance when one or several influential critics come to the conclusion that it is important.

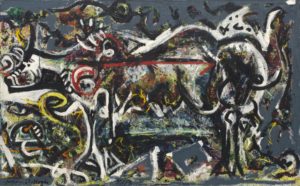

Jackson Pollock’s experience is a good example. For years, he worked in relative obscurity, producing the sort of abstractions that were popular at the time. Then the up-and-coming critic Clement Greenberg decided that one of the experimental pieces that Pollack had been doing was a work of genius… and he immediately started to be sold by Peggy Guggenheim’s prestigious Art of This Century gallery in New York City.

To give you an idea of how inexpensive Pollack’s paintings were back then, MoMA bought this piece – “The She Wolf” – for $650 in 1943:

Since the 1950s, Pollack has been included in every significant history book about modern art and has been taught in every art appreciation class. And in 2015, this “drip painting” (Number 17A, done in 1948) sold for $200 million:

Once an artist’s work is in the collection catalog of a dozen major museums, and has been selling at auctions for millions of dollars, and has made its way into the pages of respected books on art, there is virtually no chance its value will depreciate. That’s because everyone one involved with it – the collectors, the museums, dealers, and the uber-wealthy people that have bought it – have a vested interest in seeing the price rise.

Although investment-grade art can offer smart investors returns equal to or greater than stocks, and although the rules for investing in art are similar in some ways to the rules for investing in stocks, there are also differences. For example:

* The size of the market for investment-grade art is much, much smaller than the market for stocks (i.e., there are far fewer players).

* The number of factors that influence the price of investment-grade art are far fewer than the number of factors that influence stock valuations.

* Because of the above two facts, those that participate in the investment-grade art market, as a whole and even individually, have much greater control of market prices than do 99% of stock investors.

Put differently, the investible art market is a private club comprised of dealers, brokers, critics, auction houses, museums, collectors, and investors. And unlike most other markets, all of these diverse players benefit from the same thing: the gradual and steady appreciation of the art product ad infinitum over time.

Each does his part. The dealers manage the artists and their production. The brokers buy and sell it. The critics promote it. The scholars memorialize it. The museums validate it. The collectors hoard it. And the investors profit from it.

Let me put this in more pragmatic terms…

From a long-term perspective, the single most important factor in the value of a work of art is the artist’s status in the art history books. Next to that is the number of world-class museums that own and display it. Another extremely important factor is the total market “capitalization” of the artist’s work – i.e., how many millions of dollars large corporations and wealthy individuals have invested in it.

The good news for first-time art investors is that all of this information is publicly available. In fact, most of it can be obtained quickly through Google searches and auction records.

As I said, I’ve been buying and selling art for about 40 years – which is about as much time as I’ve been an active investor in the financial markets. My experience has been that, although there are some similarities (like the advantage of buying blue-chip when you can afford it and holding it long-term), investing in art feels more like investing in historical artifacts than in stocks or bonds. In other words, buying a statue by Henry Moore is more like buying a Tiffany lamp than a share of Microsoft or Walmart.

If you think about investment art as historical artifacts rather than as objects of beauty, and follow the common-sense rules one would follow when buying historical artifacts, your buying decisions will likely be sound.

MarkFord

MarkFord