Why Salvador Dalí Is the Most Counterfeited Artist in the World

In the early 1980s, soon after my first retirement, I got into the art business, buying a half-interest in an art gallery in Boca Raton. I met lots of interesting characters through this relationship – none more interesting than B, an art broker and dealer, who, among other credentials, claimed to have had some sort of exclusive deal with Salvador Dalí to sell the master’s limited edition prints and lithographs during the prior decade.

B was not an aesthete. Nor a student of art history. He didn’t speak like an art critic. Nor did he dress like one (whatever that means). Instead, like so many art dealers and brokers I have met, B struck me as a used car salesman that had figured out he could make more money and work less energetically by cultivating a customer base of a few dozen wealthy buyers and selling them more art than they could ever hope to hang in their lifetimes.

I was (still am) a big fan of Dalí. I believed then that he was a genius, and I still do. But he ruined his reputation as one of the greatest modern artists by developing an addiction to the rock and roll lifestyle, which diminished his production of oil paintings and diminished, too, the quality of everything he did.

During the 1960s, he was developing a reputation as an artistic sellout when he began to pay for his expensive and degenerate lifestyle by selling quickly executed, half-assed paintings, gouaches, and drawings. During the 1970s, he began producing signed lithographs and prints, which, he figured, could bring in more money faster than creating original pieces, however shabby.

And he was right about that. Rather than spending, say, a month on an original oil that might sell for $50,000, he could spend a day making a limited-edition lithograph of 500 pieces and another day signing them, and then sell each for $1,000.

B was one of the brokers he sold those pieces to. “In the beginning, Dalí was satisfied with editions of 200 or 300 or 500,” B told me. “But when he realized he could make much more with editions of 500, 1,500, or 2,500 – by investing only the additional time it took to sign the prints – well, he couldn’t resist the temptation.

“Larger editions were fine with me. He could make more money. And so could I. So, he’d do a print, and I’d pay him for it and then pay the printmaker to have a bunch made. I was out ten or twenty thousand dollars, but that was okay. There was a strong market for his prints. I’d make my profit after I got them signed.

“The problem was, his partying was getting crazy. When I’d visit him to get him to sign the prints, he’d be gone. For days. Sometimes for weeks! So, I told him, ‘Enough is enough!’ I told him that, from then on, he had to sign the blank paper first. He’d sign the blanks. I’d pay him. Then I’d take them to the printer. It was a perfect solution.”

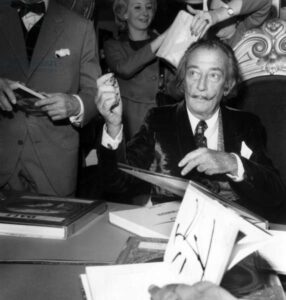

Dalí liked it, too. And he realized that B was not the only dealer that would pay him for signed blanks. So, in the 1960s, he began making similar deals with other dealers. And before long, he was signing thousands of blanks.

With aides at each elbow, one shoving the paper in front of Dalí and the other pulling the signed sheet onto another stack, there was a rumor that he once signed 1,800 sheets an hour for $72,000.

Many of these signed sheets were sold off to dealers who had no connection with Dalí, but went ahead and had the multiples printed themselves. This then led to some crooked dealers producing blank sheets with forged signatures on them.

All told, according to one expert, Dalí signed 40,000 to 60,000 blank sheets that made their way into the market. And that prompted tens of thousands more forgeries to satisfy the public’s demand for authentic Dalís.

By the time I met B, these stories were already out there, and the market for Dalí multiples had become very weak. Pieces that once sold for $10,000 were selling for $1,000. Larger edition pieces that once sold for $1,500 were selling for $150.

You can read more about all of this here.

And here.

MarkFord

MarkFord